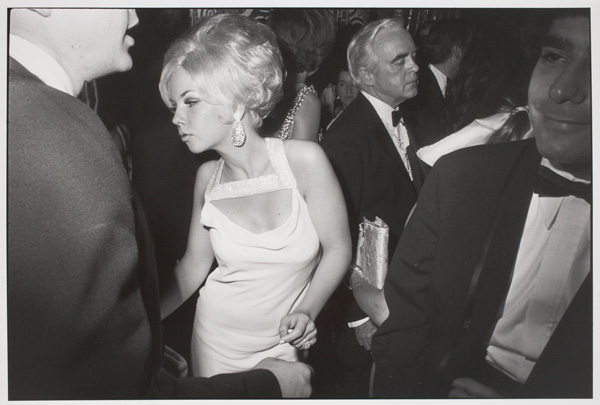

Untitled (Centennial Ball, Metropolitan Museum, New York), 1969, gelatin silver print, Gift of the Schorr Family collection, 1991.269 © The Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Holy Cross Student Responses

Maureen Dougherty

Often considered sexist because of their focus on attractive women, Gary Winogrand’s notorious collection of photographs “Women are Beautiful” are presented within various dynamic categories in Nancy Burn’s show at the WAM. The sections of the exhibit are titled “Women are objects,” “Women are fierce,” “Women are reflective,” “Women are joyful,” and “Women are more.” Some of Winogrand’s critics have called the photographs exploitative and unethical because the women in the photos did not explicitly give consent to being photographed. However, many of the women “exploited” are demonstrating arguably attention-seeking behavior, such as the woman skinny-dipping in broad daylight, or the woman sunbathing in the park wearing a revealing two-piece. Winogrand’s photographs represent several ambiguous ethical questions: Should women be treated solely as visual objects? If a woman dresses a certain way, does she merit male attention? Who is at fault: a man checking out a woman without a bra? Winogrand’s photos do not answer these questions, but perhaps they were meant to raise questions and create a discussion of how women are viewed in society. The women in Winogrand’s photos aren’t depicted as victims. They are women who are independent, and who challenge the expectations created by a male-dominated society which demanded that women be pure, good, and maternal. One could argue that Winogrand’s photographs capture the spirit of women’s liberation.

Maddie Chambers

When I first walked around the Winogrand Women Are Beautiful show, my feminist perspective informed my initial response. Most of Winogrand’s photos are taken of women in either vulgar or at least, questionable positions and seem to be taken unknown to them. This candid approach adds an element of disconnect between the viewer and the viewed, which creates awkwardness in the images themselves. When one looks at the collection as a whole, however, one begins to see it in a different light. Winogrand does not create these images; rather he points his camera and shoots what he sees. He does not ask women to sit in sexual positions or wear little to no clothing; rather he is like any other person in the crowd–only he has a camera. Taking into account Winogrand’s compulsive habit of photographing as well, one is able to see the portfolio in a different light. Given such compulsion, Winogrand’s photographs are some of the rawest of his time. This rawness mitigates the criticism that he takes personal photos of unknowing women and allows viewers to interpret them as documents of daily life. The show does a beautiful job of challenging its viewer’s eye and questioning both Winogrand’s motive in taking the photos as well as the role of the women photographed. It is easy to see the women as objectified and thereby view Winogrand as a photographer who gets “too close for comfort,” however, the show opens eyes to the representation of women at the time and how they, as subjects, decided to present themselves. After leaving the show one begins to question the role of the male gaze and the possibility of other perspectives. Would we look at these images differently if a female photographer had taken them? And if so, what would that say?

Rebecca Blackwell

When viewing the Winogrand exhibit, “Women Are Beautiful,” I was initially drawn to the bold choice of subjects that Winogrand chose for his photos, as each woman seems quite comfortable in her own skin. Winogrand was simply capturing moments that were occurring whether his camera is present or not; he never forced a photo but rather let it happen. In the photo Untitled, a topless woman is portrayed in a large crowd of people, clearly the focus of attention. Yet her demeanor seems quite relaxed and she seems empowered. No one has forced her to show her breasts in this way, yet she embraces the moment as Winogrand takes the opportunity to photograph it.

As a young woman, should these photos of women, some topless, some in unfortunate positions, bother me? Possibly. Do they? No. I believe Winogrand was capturing women in their truest of forms, strong, independent, and beautiful.

Michael Auth

Ever since its initial release, Gary Winogrand's photo collection Women Are Beautiful has generated a great deal of controversy concerning the objectifying manner in which he seemingly portrays his subjects. The only series in which he personally picked the photos himself, critics cannot decide whether his photographs, shot in his usual "snapshot" style, are simply documentarian and artistic in nature or if they carry a deeper, misogynistic theme. Curator Nancy Burns tries to address this conflict by arranging the photos according to four different categories, and it is the "Women are Fierce" grouping that I find to be most telling. Though many have argued that Winogrand, who took photos compulsively, was just practicing his simple habit of documenting the world around him, the pictures in the "Women are Fierce" node would suggest otherwise. One such photo, shot over the shoulders of a crowd, features an attractive woman glaring angrily back at the camera. Another, a woman crosses the street towards the camera in an ostentatiously aggressive manner. These photos, as with others in the series, indicate that Winogrand was not simply documenting everything that happened around him, but rather that he specifically went out of his way to capture individual scenes and subjects that caught his eye; in this case, as the exhibit shows, it is clear that he went out of his way to photograph provocatively dressed women. In doing so, it would appear that Winogrand crosses the thin line between art and perversion. The voyeuristic nature present in the pictures clearly objectifies the women in them, rather than celebrating them.

Sign up for WAM eNews

Sign up for WAM eNews