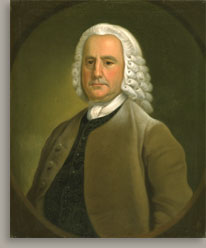

Jeremiah Theüs Jeremiah Theüs

Portrait of a Man

(Probably Isaac Holmes) , 1755

Description

In this bust-length Portrait of a Man (Probably Isaac Holmes) the sitter is placed inside a trompe l’oeil oval frame that is decorated with brown painted spandrels. Although he faces front, he is turned slightly to the viewer’s left. He wears a white wig with five tight curls visible on the proper right side of his face. More of the wig is visible on the right side, where there are vertical and horizontal curls, indicating that the wig gradually increases in length. The sitter wears a white neck cloth and a tan, collarless coat that is unbuttoned to reveal a black, patterned silk waistcoat. There are soft folds in the coat fabric. Three tan, cloth-covered buttons are visible on the left side and five buttonholes at the right. The waistcoat is fastened with six small black buttons. There is a dusting of white wig powder on the proper left shoulder of the coat.

The sitter’s face is rendered in considerable detail. His flesh tones are warm and contain areas of pink on the cheeks, chin, and forehead, which is high and smooth. A shadow from the wig falls along the left side of his face. His eyebrows are dark gray, and there are gray shadows beneath his brown eyes. The sitter’s proper right eye appears larger and rounder than his left one. There is a wart or mole on the right side of the nose. The furrow between the nose and mouth is crooked. A thin layer of gray paint around the mouth and chin suggests beard stubble. His thin lips are pressed together and are slightly downturned. He has a double chin.

Overlapping paint layers reveal that Theüs rendered the face first and then the wig and neck cloth. Although the overall ground layer is gray, this layer does not show through in the shadows under the eyes and around the mouth. These areas were given semiopaque applications of gray-brown and reddish-brown paint. There is no evidence of an imprimatura layer under any part of the figure. Typically, Theüs used little impasto or none at all, but here there is some white opaque paint on the buttons. He added gray-blue and pink paint for the shadows in the folds of the neck cloth and a darker gray paint, applied wet-on-dry. He painted the black paisley pattern on the gray waistcoat after the gray paint had dried, and he finished with the brown coat. There are no visible brushstrokes. The olive-green background varies in shade to the left of the sitter, especially near the face, where it is a lighter yellow-green.

Biography

Isaac Holmes was the son of Francis (d. 1726) and Rebecca Wharfe Holmes (d. 1731). He was born in Boston in January 1702 and baptized at the Old North Church.1 His father was the proprietor of the Bunch of Grapes tavern on the south side of King Street in Boston, and a merchant with a warehouse at Long Wharf.2 Francis Holmes also owned land in South Carolina, to which he traveled in 1702 with the power of attorney to collect money, goods, and merchandise from Robert Fenwick and Company that were owed to Henry Bridgham, a Boston tanner.3 In 1715 he was sent by the South Carolina Assembly to New England to purchase arms the colonists needed to fight the Yamasee Indians that year. By 1721, he was residing primarily in South Carolina.4

Isaac Holmes settled permanently in Charleston with his father and two of his brothers, Francis (1696/97–1728) and William (1710–1738) in about 1721. There he became a successful merchant and ship captain.5 Isaac’s brother Ebenezer (1704–1753) had remained in Boston, graduating from Harvard College in 1724.6 On January 19, 1724, Isaac married Elizabeth Peronneau (1704–1773), daughter of the Charleston merchant Henry Peronneau (1667–1743) and his wife, Desire (1680–1740). Isaac and Elizabeth had one son, Isaac, Jr. (1729–1763), and six daughters: Elizabeth (1730–1807); Anne, Sarah, Rebecca, Susannah (1739–1771), and Martha. 7

Surviving letters demonstrate the ties between the New England and South Carolina Holmes siblings. For example, in October 1728, Isaac’s brother Francis, Jr., wrote from Charleston to their brother Ebenezer, who apparently was caring for his son Francis III in Boston, asking that he "Incourage my Deare Son to his Learning & to write me." 8 And Isaac wrote home to his mother, who ran the Bunch of Grapes while her husband was in South Carolina and continued operating it after h e died, in Charleston, in June 1726.9 Two of Isaac’s sisters married Bostonians: Rebecca wed Thomas Amory (d. 1728) on May 9, 1721, and Anne married William Coffin (1699–1775) on September 3, 1722.10 Besides writing to his sisters, Isaac sent Ebenezer invoices for stock he shipped to him and corresponded about the property they jointly inherited from their father. 11

In his will, Francis Holmes, Sr., had ordered his Boston property sold but divided his South Carolina land among his four surviving sons: Francis, Jr., Ebenezer, William, and Isaac. Francis, Jr., received the 80-acre plantation on James Island, and William received the 500-acre Beach Hill plantation. The father’s half -ownership of the sloop Bumper went to Isaac. He and Ebenezer were each given half of a town lot on the water in Charleston and a lot on Penny’s Point tract in Charleston. Isaac also was given the option to buy a town lot on Broad Street.12

Isaac and Elizabeth Holmes were members of the Independent (also known during the colonial period as the Congregational and Presbyterian) Church of Charleston, where he owned a pew.13 Isaac’s in-laws, the Peronneaus, were members of the same church, which Francis, Sr., also had attended.14 In 1736, Isaac was elected an appraiser and a founding member of the Friendly Society for the Mutual Insurance of Houses against Fire.15 He served as a commissioner regulating patrols in St. Philip Parish in 1737, and from 1746 to 1748, represented the parish in the Commons House of Assembly.16 After Isaac returned from a trip to England, he was elected to the Nineteenth Royal Assembly, where he represented Prince Frederick Parish from 1749 to 1751. In addition, he was a member of the Charleston Library Society during 1750–51. Although he was appointed to the Royal Council on August 9, 1751, news of the appointment did not reach South Carolina until he was near death.17

Isaac Holmes died on November 25, 1751.18 He was buried in the Peronneau family’s plot in the yard of the Independent Church. Inscribed on the slate stone is this epitaph: "Sacred / to the memory of / the Honble ISAAC HOLMES, ESQr / a kind Husband, / tender Parent and sincere Friend / Who departed this life / November 23d 1751 / Aged 49 Years." The elaborate stone, which includes a neoclassical portrait bust, skull and crossbones, acorns, and palm branches, was carved and signed in Boston by Henry Emmes (1717–1767).19 Holmes’s estate was valued at £4,275.23.6, and it included twelve slaves.20

Analysis

Jeremiah Theüs frequently posed his sitters against an earth-toned background in an oval, framed by painted spandrels—as he did in this work. He often varied the background color so that it was lighter on one side of a sitter’s body than on the other, as in William Elliot (1757, Carolina Art Association/Gibbes Museum of Art, Charleston). Portrait of a Man (Probably Isaac Holmes) is a bust portrait. The artist was especially partial to this format, although he is known to have painted a few miniatures and three-quarter-length likenesses. For male sitters, he favored a few poses, such as the hand tucked in the waistcoat, as seen in Dr. Lionel Chalmers (1756, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). Often, he placed a hat under the arm of male sitters. Another pose characteristic of Theüs was the sitter facing front, his body turned slightly to one side, with neither hand visible; he utilized it in the present work and in Gabriel Manigault (1757, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York).

|

|

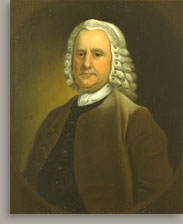

Figure 1. Jeremiah Theüs, Isaac Holmes, 1755, oil on canvas, 29 x 25 1/2 in. (73.7 x 64.8 cm), The Charleston Museum, Charleston, South Carolina, Gift of Charlotte R. Holmes.

|

|

A second portrait known as Isaac Holmes (fig. 1), also signed by Theüs and dated 1755, is almost identical to the Worcester painting. Both are set within the same Hogarth-style frames. Very specific details, including the variation in the background, the wart or mole on the nose, the folds in the coat, the wig powder, and the purple-blue shadows in the white neck cloth, are present in both likenesses, and the patterns of the waistcoats are identical. In the Charleston Museum version, however, the signature and date appear on the body of the lower-right spandrel instead of along the spandrel edge. Because of the condition of the Charleston portrait, it is difficult to compare the colors of the painted background in the two canvases.

The Worcester canvas entered the collection in 1938 as a Portrait of a Man. But the following year, the words "possibly Isaac Holmes" were added, in parentheses, when the work was published in American Portraits 1620–1825 Found in the State of Massachusetts.21 The painting had been owned by a great-great-granddaughter of William and Anne Holmes Coffin of Boston. The latter was the daughter of Francis Holmes and the sister of Isaac Holmes. Isaac Holmes’s great-great-great-granddaughter Charlotte R. Holmes gave the almost identical portrait to the Charleston Museum in 1947; she had received it after the death of her stepmother, Nellie Hotchkiss Holmes, who had received it by bequest in 1922 from her husband, George S. Holmes.22 According to records in the Frick Art Reference Library, Mrs. Holmes identified the sitter as Isaac Holmes in 1923, when the portrait was photographed, and the Charleston Museum accepted this information.23

The provenances of the Worcester portrait and of the practically identical signed-and-dated version in Charleston suggest that the man represented may be Isaac Holmes, but that cannot be proven without a doubt. It is possible, however, to eliminate other family members with Boston and Charleston connections from consideration. For example, the sitter probably is not Isaac’s father, Francis, even if Theüs copied a much earlier portrait: although the costume of the sitter in the two portraits is old-fashioned by mid-eighteenth-century standards, it would have been worn after 1726, the year Francis died.24 Isaac’s brothers Francis and William both died long before 1755, and they were too young to be the man represented in the portraits, who appears to be in or near middle-age.25 For the same reason, the sitter is not Isaac Holmes, Jr., who would have been only twenty-six in 1755, the year inscribed on the canvas. Isaac’s brother Ebenezer was closer in age to Isaac, but he died in 1753.

In her 1958 article on the identical Theüs portraits, Worcester Art Museum curator Louisa Dresser evaluated the theories proposed to identify the sitter in the two portraits. She demonstrated the strength of the ties between the New England and South Carolina Holmes families and concluded that the sitter must have had links to both Boston and Charleston. She supported Theüs scholar Margaret Middleton’s suggestion that the sitter was Isaac Holmes and that one of the portraits was sent to New England for Isaac’s sister Anne. Furthermore, Dresser recognized that for Isaac Holmes to be the sitter, both portraits must be posthumous: Theüs would have had to have copied an original portrait from life for both these 1755 portraits, since Isaac Holmes had died four years earlier. 26

|

|

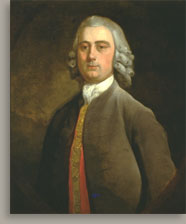

Figure 2. William Keable, Thomas Smith, Jr., 1749, oil on canvas, 29 3/4 x 24 1.4 in. (75.6 x 61.6 cm), Collection of Robert Goodwyn Rhett, Charleston, South Carolina.

|

|

It is possible that Isaac Holmes sat for a portrait during his lifetime that Theüs copied after the sitter’s death. As he explained in a letter to his brother Ebenezer, Isaac planned to sail to England in March 1749: "I am now to Inform you that I am Goeing to London ocasion’d by my being much out of order for a long Time and as I expect the greatest Benefitt from the Sea."27 A fellow Charlestonian, Henry Laurens (1724–1792), reported in an April 20, 1749, letter from Deal, England: "I am glad to hear Mr Smith and Mr Holmes recover their Health so well. I hope soon to have the pleasure of communicating the agreeable news to their friends in Carolina."28 Isaac’s traveling companion was another Charleston man, Thomas Smith, Jr. (1720–1790).29 Smith had sat for the British artist William Keable (about 1714–1774) during his stay in England (fig. 2), and Isaac Holmes might have, too.30 According to Peter Manigault, who chose Allan Ramsay (1713–1784) to paint his likeness, other Charlestonians traveling abroad patronized Keable. "I was advised to have it drawn by one Keble," he wrote, "that drew Tom Smith & several others that went over to Carolina."31 Thomas Smith, Jr.’s sister-in-law Anne Loughton Smith (1722–1760) was among Keable’s sitters (1749, Carolina Art Association/Gibbes Museum of Art, Charleston), and it is possible that her husband, Benjamin Smith (1718–1770), joined her.32 Perhaps Isaac Holmes was one of several Charlestonians who posed for Keable in 1749, and then Theüs copied the resulting portrait twice in 1755 for family members in Boston and Charleston.33

Keable’s Thomas Smith, Jr. offers several good points comparison with Portrait of a Man (Probably Isaac Holmes) and the Charleston version. Yet Theüs’s signature is authentic; the work could be a Theüs copy of a Keable, but it is certainly not by Keable.34 The Smith and Holmes pictures have similar dimensions, and the sitters are painted inside trompe l’oeil frames with spandrels. As in Portrait of a Man (Probably Isaac Holmes), the background in Thomas Smith, Jr. is lighter on the left side than on the right. The outline of the coat along the proper left arm in both works is loosely rendered. Although Smith’s coat collar is higher than Holmes’s, the treatment of the buttonholes is similar. With the exception of the Worcester and Charleston paintings, no other Theüs portraits with wig powder have been located, and the substance is present on Smith’s shoulder. Since Theüs did not customarily render wig powder, its appearance in the two Holmes portraits supports the idea that he was copying an earlier portrait of Holmes that had it. Smith’s wig is shorter than Holmes’s, but the combination of horizontal and vertical curls is present in all three portraits. The major difference between the portrait of Thomas Smith, Jr., and those that are probably of Isaac Holmes is that the former is much more painterly and has visible brushstrokes; all of Theüs’s known portraits, including Portrait of a Man (Probably Isaac Holmes), have blended brushstrokes.

The differences between the Worcester portrait and other Theüs works further bolster the notion that it might be a copy of a Keable portrait. Theüs’s palette was often brighter, even for portraits of men, than in Portrait of a Man (Probably Isaac Holmes). For instance, the background of the simple bust portrait William Elliot (1757, Carolina Art Association/Gibbes Museum of Art, Charleston), contains some blue-green, and although the sitter’s coat is brown, the waistcoat is a bright blue. Theüs scholars commonly note that the faces of his sitters, which, although somewhat individualized, often share a set of characteristics that creates an impression of sameness.

|

|

| Figure 3. Jeremiah Theüs, Susannah Holmes (Mrs. Thomas Bee), 1758, oil on canvas, 35 x 30 in. (88.9 x 76.2 cm), The Charleston Museum, Charleston, South Carolina, Gift of Charlotte R. Holmes. |

|

Close-set eyes, long noses, full upturned lips, and dimpled chins are the norm. Significantly, in this likeness the facial features are distinct. The sitter’s eyes are not close-set but appear to be of two different sizes, and his thin lips curl downward. There is a wart or mole on the right side of his nose, and his chin is heavily wrinkled.

Since other Holmes family members patronized Theüs, including two of Isaac’s daughters, it is conceivable that the family might have chosen the artist to make two copies of a portrait of Isaac Holmes. Elizabeth Holmes (1730–1807) married Samuel Brailsford (1728–1800) on April 7, 1750, and she and her husband probably sat for Theüs around the time of the nuptials; their companion portraits (both in private collections) have the same dimensions and trompe l’oeil frames.35 Susannah Holmes (1739–1771) married Thomas Bee (1739–1812) on May 5, 1761, but her portrait was painted before her marriage (fig. 3). It is signed and dated "Theüs 1758" on the spandrel in the lower-left corner. She sat for her portrait at the same time as did her future mother-in-law, Susannah Simmons Bee, whose husband, Colonel John Bee, had died in 1749.36

Notes

1. Boston Births 1894, 15. Isaac was baptized at Boston’s Second Church (Old North Church), where his mother was a member, as were eight of his siblings; see Robbins 1852, 254. Four other siblings were baptized at the Brattle Street Church, where their father was admitted as a member on November 3, 1706; see Brattle Square 1902, 96, 128, 130, 131, 133.

Rebecca Wharfe was the daughter of Nathaniel and Rebecca Mackworth Wharfe of Falmouth, and she was admitted as a member of Second Church in Boston in January 1690. Rebecca Wharfe married Francis Holmes on February 15, 1693. See Noyes 1983, 742; Meredith 1901, 90–91.

2. See Boston News-Letter, December 8–15, 1712; and Will of Francis Holmes, Suffolk County docket no. 5258.

3. Moore 1978, 224. For Robert Fenwick, see South Carolina House of Representatives 1977, II, 246–47.

4. Genealogical chart for the descendants of Francis Holmes, CG-173, South Carolina Historical Society, Charleston, McCrady 1897, 544.

5. South-Carolina Gazette, July 27, 1738; Francis Holmes, Charleston, to Ebenezer Holmes, Boston, October 17, 1728, David S. Greenough Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, box 2.

6. For Ebenezer Holmes, see Sibley and Shipton 1945, VIII, 368–71.

7. Hutson 1984, 52; Clemens 1973, 131. Although Hutson records Issac’s wedding date as January 19, 1723 (rather than 1724), the discrepancy is probably due to the change from the Julian to the Gregorian calendars.

8. Francis Holmes, Charleston, to Ebenezer Holmes, Boston, October 17, 1728, David S. Greenough Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, box 2.

9. The month of Francis Holmes’s death is given as June in Brattle Square 1902, 96. As a widow, Rebecca Wharfe Holmes purchased her husband’s brick house on King Street as well as his warehouse on Long Wharfe. Meredith 1901, 89. Rebecca Holmes was listed as an "inholder" in the inventory of her estate taken on June 14, 1731, Suffolk County docket no. 6118. See also Suffolk County Deeds, vol. 41, p. 138 and vol. 44, p. 27.

10. Meredith 1901, 91.

11. Isaac Holmes, Charleston, to Mrs. Rebekah Amory, Boston, April 11, 1730, Amory Family Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, vol. 1, 1698–1784; Isaac Holmes, Charleston, to Mrs. Rebekah Holmes, Boston, August 24, 1730, Amory Family Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, vol. 1, 1698–1784; Isaac Holmes, Charleston, to Ebenezer Holmes, Boston, May 9, 1744, David S. Greenough Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, oversize material box 1; Isaac Holmes, Charleston, to Ebenezer Holmes, Boston, February 17, 1748, David S. Greenough Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, box 4; Isaac Holmes, Charleston, to Ebenezer Holmes, Boston, February 8, 1744/45, David S. Greenough Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, oversize material box 1.

12. See Suffolk County Will, docket no. 5258, 1726; and Moore 1960, 114–15.

13. Known today as the Circular Congregational Church, this congregation was founded between 1680 and 1690—during the period when Charleston was first being settled—by English Congregationalists, Scots Presbyterians, and French Huguenots. The church did not have an official name but was variously referred to as Independent, Congregational, and Presbyterian throughout the colonial period. See Edwards 1947, 3, 5; and Charleston Yearbook 1882.

14. Besides leaving money in his will to Benjamin Coleman and William Cooper, ministers of the Brattle Street Church in Boston, Francis Holmes, Sr., gave ten pounds to the Reverend Nathan Bassett. See Suffolk County Probate Record, docket no. 5258. Originally from Roxbury, Massachusetts, Bassett was the pastor of Circular Church from 1724 until his death in 1738. See Edwards 1947, 157. For Henry Peronneau’s connection to the church, see Hirsch 1962, 99. Isaac’s brother Francis died in 1727, but his wife and family had pew number twenty-three in 1732. Charleston Yearbook 1882, 375.

15. For the Friendly Society, see South-Carolina Gazette, January 31–February 7, 1735/36; "Historical Notes: An Early Fire Insurance Company," South Carolina HIstorical and Genealogical Magazine, no. 1 (January 1907): 46–53. At a town meeting in 1737 Isaac Holmes was appointed one of five fire masters. South-Carolina Gazette, March 26–April 2, 1737. South Carolina HIstorical and Genealogical Magazine.

16. South Carolina House of Representatives 1977, II, 327–28.

17. Ibid. On October 7 the Charleston newspaper reported, "We hear, that Isaac Holmes, Esq. (now at New-York for the Recovery of his Health) is appointed a Member of his Majesty’s Honourable Council, in the Room of Col. Joseph Blake, lately deceased." See South-Carolina Gazette, October 3–7, 1751.

Although the reason for Isaac’s visit to New York is not mentioned, Francis Holmes III informed his Uncle Ebenezer, "Your brother is going to Rhode Island with Alexr Peronneau they dont propose to See Boston but goe from thence to [New] York they will sail in about a month." See Francis Holmes, Charleston, to Ebenezer Holmes, Boston, April 5, 1751, David S. Greenough Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, box 5.

18. South-Carolina Gazette, November 25, 1751.

19. I thank Pat Spaulding, historian/archivist, Circular Congregational Church, Charleston, for sharing her research on the Holmes family gravestones with me. For Emmes, see Combs 1986, 150–54; and Chase and Gabel 1997, I, 63–127.

20. Will of Isaac Holmes, 1751, Charleston County Wills, vol. 6, pp. 583–89;

Inventory of Isaac Holmes, 1752, South Carolina Inventories, vol. R (1), pp. 358–64, South Carolina Department of Archives and History, Columbia.

21. Receipt, March 31, 1938, curatorial files, Worcester Art Museum; American Portraits 1939, II, 491.

22. Dresser 1958, 43–44.

23. Mrs. George S. Holmes later referred to the sitter as Francis Holmes, but the original identification was maintained. Frick Art Reference Library Photograph Mount,

121–15 F; Lydia Dufour, Frick Art Reference Library, to Laura K. Mills, September 23, 1999.

24. According to the costume expert Lynne Bassett, the fashion dates to about the 1730s. The short, full-bottomed wig was not fashionable by mid-century, when wigs were curved away from the face, as in Gabriel Manigault (1757, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), or were shorter. Lynne Z. Bassett, Old Sturbridge Village, to Laura K. Mills, July 16, 1999.

25. However, the will of Isaac’s brother Francis, Jr., dated June 12, 1727, and proved January 16, 1728, mentions two portraits to be given to Francis III. One was of Francis, Sr., and the other was of himself. See Moore 1960, I, 134–35. These portraits have not been located.

26. Dresser also suggested that Anne Holmes’s husband, William Coffin (1699–1775), might be the sitter, if it could be proved that he visited Charleston. Dresser 1958, 44. The Coffin family ties to Charleston persisted with the grandson of William and Anne Holmes Coffin. Their son William (b. 1723) had a son Ebenezer (b. 1763), who moved to South Carolina and married Mary Matthews in 1793. Appleton 1896, 42, 45.

27. Isaac Holmes, Charleston, to Ebenezer Holmes, Boston, February 17, 1748, David S. Greenough Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, box 4.

28. Henry Laurens, Deal, England, to William Store, April 20, 1749, as quoted in Hamer 1968, I, 239.

29. For Thomas Smith, Jr., see South Carolina House of Representatives 1977, II, 641–43.

30. For the portrait Thomas Smith, Jr., see Gibbes Museum of Art 1999, 94–95. For Keable, see Waterhouse 1981, 203; and Ingamells 1997, 565.

31. Peter Manigault, London, to Ann Ashby Manigault, Charleston, April 15, 1751, as quoted in Webber 1930, 278.

32. Ellen Miles suggested that the portrait Benjamin Smith (n.d., Albrecht-Kemper Museum of Art, St. Joseph, Missouri), presently attributed to John Wollaston, might be by Keable. Gibbes Museum of Art 1999, 94–95. There is also a Theüs canvas, Benjamin Smith (n.d., Carolina Art Association/Gibbes Museum of Art, Charleston), which appears to be a copy of the Albrecht-Kemper portrait. In contrast to the nicely rendered hand in the latter picture, most of the hand in the Gibbes Museum portrait is awkwardly tucked into the waistcoat, in typical Theüs fashion.

33. The files for William Keable at the Witt Library, Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London, and the Heinz Archive and Library, London, contain no references to a Keable portrait of Isaac Holmes.

34. Many Theüs portraits are signed and dated in reddish-brown paint, as is Portrait of a Man (Probably Isaac Holmes). See, for instance, Sarah Procter Daniel Wilson (Mrs. Algernon Wilson) (1756, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Winston-Salem, North Carolina), Ann Ashby Manigault (Mrs. Gabriel Manigault) (1757, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), and Susannah Holmes (Mrs. Thomas Bee) (1757, Charleston Museum).

35. For Brailsford, see South-Carolina Gazette, April 2–9, 1750; and South Carolina House of Representatives 1977, III, 93–94. The portrait Elizabeth Holmes Brailsford is currently on loan to the Historic Savannah Foundation and on display at the Davenport House, 119 Habersham Street, Savannah.

36. Charlotte R. Holmes also gave the portraits of Susannah Holmes and Susannah Simmons Bee to the Charleston Museum. For Thomas Bee, see South Carolina House of Representatives 1977, II, 69–72. |