| John Wollaston Born England, active 1742–75. John Wollaston was one of several painters who introduced English rococo portraiture—with its emphasis on graceful poses, pastel colors, and skillfully rendered costumes—to the American colonies. Although the record of his travels is incomplete, he seems to have spent the better part of several decades living and working in various mid-Atlantic cities as well as in Southern cities and on plantations. Arriving in New York in 1749, he stayed for two years, worked briefly in Philadelphia in 1752, and, by the winter of 1753, moved on to Annapolis, Maryland. There and in Virginia, his next destination, he produced dozens of portraits. He returned to Philadelphia in 1758, but his exact whereabouts between that year and September 1765, when he appeared in Charleston, South Carolina, are a matter of speculation. He left Charleston for England in the spring of 1767 and evidently never returned to America. John Wollaston was possibly the son of the London portraitist John Woolaston (about 1672–1749), whose Thomas Britton (1703) is in London’s National Portrait Gallery.1 According to the English author Horace Walpole (1717–1797), the elder Woolaston married the daughter of an attorney named Green and had several children "of which one son followed his father’s profession."2 In addition to a group of portraits made in England, John Wollaston’s depiction of the New Yorker William Smith, Jr. (New-York Historical Society, New York) helps link the artist to London. A label on back of the canvas notes that the work was painted in New York in 1751 by "Johnannes Wollaston Londoniensis."3 The American artist Charles Willson Peale, in an 1812 letter to his son Rembrandt, recalled that John Wollaston "had some in[s]tructions from a noted drapery painter in London and soon after took his passage to New york."4 The art historian Ellen Miles has suggested that Wollaston might have studied with Joseph van Acken (1709–1749), a highly successful drapery painter in the London of the 1740s. Van Acken completed the costume and background in portraits by the leading British rococo artists Allan Ramsay (1713–1784) and Thomas Hudson (1701–1779). Because Wollaston’s and Hudson’s paintings have some traits in common–including similar poses and props and an interest in rendering the textures of brightly colored costumes–it is probable that Wollaston was familiar with van Acken’s work. It is also probable that, if Woolaston and Wollaston were in fact father and son, the younger artist would have been trained by the senior one.5

Citing the trademark aspects of Wollaston’s portraits, various scholars have pointed out his sitters’ upturned lips and heavily lidded oval eyes—often terming them almond-shaped. These and other stylized features were not unique to Wollaston but were employed by some of the leading English rococo portraitists of the day, particularly Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723) and his followers, including Thomas Hudson, Allan Ramsay, and Richard Wilson (1713–1782).8 Also like these artists, Wollaston borrowed poses and costumes from mezzotints, with the result that many of his sitters shared similar poses and costumes. For instance, to position the sitters’ hands in his portraits Clara Walker Allen (Mrs. William Allen) (about 1755–57, Brooklyn Museum of Art) and Cornelia Beekman Walton (Mrs. William Walton) (about 1750, New-York Historical Society, New York), he probably referred to John Smith’s (1652?–1742) mezzotint after Kneller’s Her Royal Highness Princess Ann of Denmark (1692, New York Public Library, New York).9 A popular pose for male sitters in English rococo portraits featured one hand tucked in the waistcoat, with a hat placed under that arm. Wollaston utilized this convention, for example, in Richard Randolph Jr. (about 1755–57, Muscarelle Museum of Art, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia). Whether he copied the pose from a mezzotint or recalled it from portraits he had seen in London is not known—but it is clear that he repeated it often.

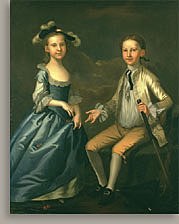

As he did with poses and costume, Wollaston appears to have repeated certain props in a number of images. Many of his likenesses of Virginia women, such as Betty Harrison Randolph (Mrs. Peyton Randolph, the Speaker) (about 1755–57, Virginia Historical Society, Richmond), include fans. The little girls in the portraits Rebecca Calvert (1754, Baltimore Museum of Art), Elizabeth Randolph (about 1755–57, Virginia Historical Society), and Mary Lightfoot (about 1755–57, Daughters of the American Revolution Museum, Washington, D.C.) all hold dolls. Also, Wollaston consistently used marble tables in his pictures, beginning with Sir Thomas Hales (fig. 1) and at least up through the Charleston portrait Ann Gibbes (Mrs. Edward Thomas) The subject of that painting holds a black velvet mask, an unusual accessory in colonial American likenesses but very popular in English rococo portraits. The mask, as well as the dolls and marble tables, in Wollaston’s images further point up the links between his work and that of his London contemporaries. Thomas Hudson, for example, used these props in certain of his canvases.11 Although most of Wollaston’s works are bust- and three-quarter-length views of individual sitters, there are some exceptions. His only known full-length portraits are of children, such as Master Beekman (about 1749–52, Art Institute of Chicago). He painted three double portraits of siblings, including Warner Lewis II and Rebecca Lewis (fig. 3), in which he once again looked to the Rubens portrait of Helena Fourment as the basis for the female sitter’s costume.12 He also produced double portraits of mothers and children, such as Mrs. Perry and Her Daughter, Anne (n.d., Philadelphia Museum of Art).13 Although two larger group portraits are attributed to Wollaston, Family Group (about 1750, Newark Museum, Newark, New Jersey) and Mother with Two Daughters (n.d., Montclair Art Museum, Montclair, New Jersey), recent scholarship suggests that he did not paint the latter work. The treatment of the lace in that portrait is not typical of Wollaston. Also, it has been determined that the costumes in Mother with Two Daughters date before 1749; the artist arrived in New York in the spring of that year.14 It appears that Wollaston remained there through the spring of 1752.15 At that time, the city had no resident portraitist but was instead occasionally visited by itinerant painters. There was a market for Wollaston’s fashionable English portraiture in New York, and about fifty portraits survive from his stay there.16 The apparel that many of Wollaston’s female New York sitters wear is similar, although some details and colors vary.17 For instance, in the oval format, bust-length portraits Catherine Harris Smith Pemberton (Mrs. Ebenezer Pemberton) (fig. 4) and Margaret Tudor Nicholls (Mrs. Richard Nicholls) (fig. 5), the highlights in the folds of the dresses are practically identical, as are the peaks at the top of the two lace caps. Mrs. Pemberton’s dress is silvery gray, and Mrs. Nicholls’s is buff-colored. The former has a bow on her fichu, but the latter does not.18 Both women are turned slightly to the viewer’s left.

In Philadelphia, as he had in England and New York, Wollaston painted bust-length and three-quarter-length portraits. His clients included subscribers to the Philadelphia Dancing Assembly, such as Richard and William Peters, Thomas Lawrence, William Plumsted, and Charles Willing.21 The latter four were mayors of Philadelphia. Wollaston’s portraits appear to have had an impact on at least two colonial American painters. During his time in Philadelphia, he influenced native-born artists such as Benjamin West and John Hesselius (1728–1778).22 Included in a Wollaston tribute by the Philadephian Francis Hopkinson that appeared in the American Magazine in 1758 was a verse instructing the young Benjamin West to "Let [Wollaston’s] just precepts all your works refine,/Copy each grace, and learn like him to shine."23 West seems to have paid heed. Scholars have remarked, for example, on the Wollaston-like treatment of the drapery highlights, pose, and eyes in West’s Elizabeth Peel (about 1757–58, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia).24 By the late 1750s, John Hesselius, too, had adopted at least several features of Wollaston’s work. These included giving his sitters almond-shaped eyes and highlighting drapery to render the texture of the fabric, as in Samuel Lloyd Chew (1762, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Winston-Salem, North Carolina). In early 1753 Wollaston arrived in Maryland, where he painted about sixty portraits for the Bordley, Calvert, Carroll, Dulany, Johns, and Key families.25 One sign that his portraits of Maryland women were favorably received is the poem "On Seeing Mr. Wollaston’s Pictures, in Annapolis," penned by a Dr. T. T. and published in the March 15 issue of the Maryland Gazette:

The Calvert family mansion, located in St. Mary’s County on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, was probably Wollaston’s last stop in Maryland. It is likely that the close ties between the families of sitters in Maryland and Virginia brought the artist commissions from farther south.27 Working in Virginia from about 1755 until October 1757, Wollaston painted some sixty portraits, about the same number he had produced in Maryland. Most of this work was done for four households of the prominent Randolph family, including a copy of an older likeness, by an unknown artist, of William Randolph II (1681–1741) (about 1755–57, Virginia Historical Society, Richmond).28 Wollaston’s Virginia portraits were typically large, three-quarter-length views that often included landscape or interior settings. The formats of these canvases varied little from those he had done in New York, and both groups of work show his connection with the London portrait scene of the 1740s. For instance, as the art historian Ellen Miles has demonstrated, the Virginia portrait Colonel Warner Lewis (about 1755–57, Muscarelle Museum of Art, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia) is practically identical to the New York portrait William Walton (about 1750, New-York Historical Society, New York). The subjects strike the same pose in both pictures: each man leans one arm on a table and places the other arm, slightly bent, with hand on hip and the second and third fingers extended, at the waist, near the waistcoat pocket. This was a pose that Thomas Hudson and Joseph van Acken utilized often.29 The pose also is seen, in reverse, in Wollaston’s Virginia portraits Colonel John Tayloe, II (about 1755–57, private collection) and Colonel Peter Randolph (about 1755–57, private collection). The last record of Wollaston’s presence in Virginia is a receipt indicating that on October 21, 1757, Mrs. Daniel Parke Custis (later Mrs. George Washington) paid him fifty-six pistoles for three portraits: one of herself, one of her husband, Daniel Parke Custis, and a double portrait of their two children, John Parke Custis and Martha Parke Custis (Washington and Lee University, Lexington, Virginia).30 After leaving Virginia, Wollaston returned to Philadelphia. He was painting portraits there by September 1758, the month that Francis Hopkinson’s above-noted tribute to the painter was published. Its title, "Verses Inscribed to Mr. Wollaston," included an asterisk, which led the reader down to an explanation that the artist was "An eminent face-painter, whose name is sufficiently known in the world."

The only other documented evidence of Wollaston’s second stay in Philadelphia is a May 1759 invoice from Henry Clinton, charging a Doctor Richard Hill for "a frame for Patsy’s picture costing one pound ten shillings and for her picture to Woolaston costing eight pounds ten shillings."32 Wollaston’s whereabouts from mid-1759 until September 1765, when he is known to have been in Charleston, South Carolina, are not recorded. At one point, it was theorized that he was in the East Indies for part of that period, but scholars no longer credit this idea.33 There is at least one piece of evidence, however, that he spent some of this time in the West Indies. On July 31, 1775, John Baker, who had been solicitor-general of the Leeward Islands in the West Indies in the 1750s, noted in his diary that "Mr. Woollaston, the painter, came up to me before dinner [at Mr. Smith’s] and claimed our acquaintance at Mrs. Cottle’s, St. Kitt’s in 1764 or 1765."34 (St. Kitts, officially called St. Christopher, is part of the Leeward Islands chain.) As it happens, the Baker diary entry is the last mention of Wollaston on record; it is not known when or where he died.

During his stay Wollaston no doubt encountered the Swiss-born Jeremiah Theüs. Theüs had been Charleston’s principal resident portraitist since 1740, encountering little competition in that role. Like Wollaston, he frequently selected his sitters’ costumes and poses from mezzotints, or perhaps from other portraits. He, too, used similar compositions and costume for various sitters.36 For instance, the Theüs portraits Catherine Cordes Prioleau (Mrs. Samuel Prioleau III) (about 1766, United Missouri Bancshares Inc., Kansas City, Missouri) and Henrietta Isabella Sommers Dart (Mrs. John Dart) (about 1772, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) are practically identical, including the five strands of pearls at the neck and the two strands of pearls looped over the bodice of the dress. Theüs used ermine trim, a Turkish-style sash, and jeweled fastenings on the bodice of the dress in Mary Elizabeth Bellinger Elliott (Mrs. Barnard Elliott, Jr.) (about 1766, Carolina Art Association/Gibbes Museum of Art, Charleston) as well as in another group of related portraits. This interest in turquerie and aristocratic costume reflects another mid-eighteenth-century London fashion in portraiture; indeed, Wollaston had been using ermine for at least ten years before arriving in Charleston.37 Although both Theüs and Wollaston worked from mezzotints and could have looked at similar sources, it is possible that some of the similarities seen in the costumes and poses they used reflected Wollaston’s influence on Theüs. By February 1767, Wollaston, preparing to leave Charleston, declared his plans in the South Carolina Gazette:

The Manigaults, who had posed for Theüs in 1757, do not appear to have patronized Wollaston. But they did invite him to dinner again, about six weeks before he left.39 On May 29, 1767, he departed for England on the Portland, having painted at least twelve portraits in Charleston.40 In all, Wollaston had produced more than two hundred portraits during his years in the American colonies. Notes 2. For "J. Woolaston," see Walpole 1862, II, 620–21. 3. Bolton and Binsse 1931, 32. 4. Peale admitted in the same letter that his memory was not perfect. See Charles Willson Peale, Germantown, Pennsylvania, to Rembrandt Peale, October 28, 1812, as quoted in Miller 1991, III, 173; and "Memoirs of Charles Willson Peale from his original manuscript with notes by Horace Wells Sellers," Peale-Sellers Papers, American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia. 5. Saunders and Miles 1987, 177. For Hudson and van Acken, see Miles 1979 and Steegmann 1936. 6. A mezzotint of the portrait bears the inscription "John Wollaston, Junr. Pinxt., 1742." An earlier portrait entitled James Monk (private collection) is signed and dated, "J. Wollaston 1733." The work warrants further study to determine if it is by John Wollaston or by the man who presumably was his father. For this portrait, see Weekley 1976, 11–12; Craven 1975, 22; and Montreal Museum of Fine Arts 1967, cat. no. 114. 7. Groce 1950, 261–68. 8. Craven 1975, 24–25. 9. Belknap 1959, 294–95. 10. For other works that drew from the Fourment portrait, see the chapter "The Dress of Rubens’ Wife" in Ribeiro 1984. 11. For Hudson’s use of the mask, see his portrait of the Virginian Robert Carter (1753, Virginia Historical Society, Richmond). For the doll, see The Courtenay Children (n.d., Earl of Devon’s Trust). For the marble table, see Sir John Willes (1744, National Portrait Gallery, London). 12. The two other double portraits are John Parke Custis and Martha Dandridge Custis (1757, Washington and Lee University, Lexington, Virginia) and Mann Page III and Elizabeth Page (1755–57, Virginia Historical Society, Richmond). 13. There is another Wollaston double portrait of a Virginia mother, Rebecca Plater Tayloe, and her daughter in a private collection (about 1755–57). 14. For these portraits, see Craven 1975, 30, 31, and Montclair Art Museum 1989, 60, 61. 15. In "The Art of Painting," an anonymous essay published in England in 1748, Wollaston’s name was listed among the fifty-seven artists who were then working in England. See Whitley 1928, I, 104. The first record of Wollaston’s presence in New York is a court document identifying him as a witness to a tavern brawl on June 23, 1749. See Craven 1975, 25. Bolton and Binsse cited an April 1, 1752, record for Wollaston in the minutes of the Vestry Board of New York’s Trinity Church showing that he was commissioned to copy "the late Revd Commissary Vesey’s picture, a half length, in order to be placed in the Vestry Room." Bolton and Binsse 1931, 30. This suggests that he was still in New York in the spring of 1752. 16. Craven 1975. 17. Kidwell 1999, 88. 18. See the following additional related portraits of women in New York: Anna French Reade (Mrs. Joseph Reade) (about 1749–52, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), Lady of the Philipse Family (about 1750), and Catharine de Peyster Livingston (Mrs. John Livingston) (about 1750–52) (both New-York Historical Society, New York). 19. On October 20, 1752, Hamilton wrote in his cashbook, "pd. Mr. Woolaston for 2 half length Pictures __ 36—." James Hamilton Papers, 1733–1783, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, box 1, no. 1, Cashbook, 1739–1757, 22. Hamilton also paid "Wollaston" an additional seventeen pounds on September 2, 1752. See cashbook, 21. 20. For a list of portraits Wollaston painted in Pennsylvania, see Weekley 1976, 227. 21. Balch 1914, 338–39. 22. For Wollaston’s influence on West and Hesselius, see Weekley 1976, 58–67. 23. H[opkinson] 1758, 607–8. 24. Von Erffa and Staley 1986, 542–43. West’s early portraits Ann Inglis (about 1757, Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington) and Thomas Mifflin (about 1758–59, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia) were previously attributed to Wollaston. 25. Weekley 1976, 17, 233, 234. 26. Maryland Gazette, March 15, 1753. 27. Weekley indicates that Rebecca Calvert (1754, Baltimore Museum of Art) is the latest dated Maryland portrait. She also suggests the ties between the Maryland patrons and those who commissioned portraits from Wollaston in Virginia (1976, 32–35). 28. Meschutt 1984. 29. Saunders and Miles 1987, 179. For the Hudson and van Acken portraits, see Miles 1979, cat. nos. 27, 42, and 43. 30. The receipt is in the Martha Washington Collection, Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, and is reproduced in Weekley 1983, 26. 31. H[opkinson] 1758, 607–8. 32. Daybook of Samuel P. Moore, Library Company of Philadelphia Collections, as quoted in Weekley 1976, 17–18, 27 n. 57. 33. Yorke 1931, 324. Weekley pointed out that there was extensive trade between Charleston and the West Indies, with ships from the islands arriving in the Southern port almost daily. Thus Wollaston could readily have traveled between the two places (1983, 26). Groce reported that a John Wollaston was appointed to be a "writer" for the British East India Company in London on November 11, 1757, and later a magistrate in a court of Calcutta (1952, 141–42). But Weekley determined that the John Wollaston recorded in the East Indies was born in 1740 and was not the artist (1976, 18–19). 34. Yorke 1931, 324. 35. Ann Ashby Manigault diary, September 27, 1765, as quoted in Webber 1919a, 209. 36. Severens 1985, 56–70. 37. Wollaston added ermine trim to the portraits of two Maryland sitters: the material is draped across the front of the dresses in Elizabeth Calvert (Mrs. Benedict Calvert) (1754, Baltimore Museum of Art) and Eleanor Carroll (Mrs. Daniel Carroll) (about 1753–54, unlocated). 38. Wollaston’s notice appeared in the South Carolina Gazette, January 19–February 2, 1767, and in the Supplement to The South Carolina Gazette, February 9, 1767. 39. On April 12, 1767, Mrs. Manigault noted in her diary, "Mr. King, Walter, and Wooleston at dinner," as quoted in Webber 1919b, 257. 40. His departure was reported in the South Carolina Gazette, May 11–June 1, 1767. |