Benjamin West

Benjamin WestPharaoh and His Host Lost in the Red Sea,

1792 and after 1800

Description

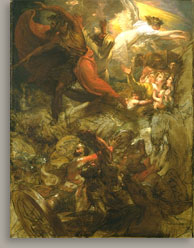

Pharaoh and His Lost Host in the Red Sea is a vertically organized, partially finished history painting. West created the composition with a black line drawing and added brown tones to create modeling. Over this underdrawing, West selectively added red, yellow, blue, and white to the main figures and sky.

At the upper left, Moses is shown in a striding position, with his right foot firmly planted and his left lifted slightly off the ground. His head is shown in left profile, and his hair and long beard blow in the wind. The billowing red fabric in which Moses is draped is also swept to the left by the draft. Moses gestures dramatically. His left hand forms an arc above his head, and his right hand stretches on a diagonal toward the left edge of the canvas, creating a line that is continued by the staff in his right hand.

Behind and the to right of Moses, Aaron is depicted with his back to the viewer. His face is turned up, and his arms are raised toward heaven. Aaron's fervent action makes it appear as though he is falling toward the picture plane. West cloaked Aaron in a yellow cloth that covers his body, arms, and head.

To the right of Aaron, a winged angel points toward the right side of the painting. The angel has yellow curls and a white robe that is secured by a belt placed high on the waist. Whereas the upper left portion of the sky is filled with dark clouds, the sky behind the angel is illuminated by brilliant red and yellow light. Below the angel's outstretched arms, West placed a group of nine closely huddled figures–three men, three women, and three children. In the upper register of this cluster of figures, two young men carry a round object and a box that is inscribed with writing. The young men move toward the right edge of the composition; to their right, an old man faces three-quarters left, thereby directing the viewer's attention back to the center of the canvas. Just below them are three women, each facing left. The one who is farthest left points toward heaven; the one in the middle extends her right arm toward Moses and Aaron; and the woman at right clasps her hands in prayer in front of herself. The woman in the middle is draped in the same shade of yellow as Aaron; she holds an infant in her left arm, and a second child reaches for her waist. A third child, whose face is framed by the sole of Moses's left foot, turns in right profile toward the women.

The lower half of the canvas is filled with the pharaoh and his army, whose bodies are strewn about and whose faces show terror. The crown of the pharaoh, the most prominent figure in the lower portion, identifies his royal position. West arranged his body on a twisting diagonal from the lower left to the center of the composition. The bottom left corner depicts a wheel, presumably from the disabled chariot of the pharaoh. Just in front of the pharaoh, at the bottom center of the painting, a helmeted soldier raises his right hand in an echo of Moses's gesture and puts his left hand behind himself to brace his fall. At least five other men and three horses are also crowded into the chaotic lower half of the image. Foaming water is visible at the left and right sides, and a number of spear points below Moses suggest that many more soldiers have already been carried away by the waves.

Between the upper and lower halves of the composition, a group of liberated Israelites form a procession from left to right. These figures are on a much smaller scale than the others, suggesting that they are in the distance. The Israelites include men and women carrying their possessions on their heads and backs and leading camels on their journey.

Patron Biography

George III (1738-1820) became the king of England in 1760 and reigned over Great Britain during the American Revolution.1 In addition to his active role in statesmanship, the king attached considerable importance to patronage of the arts, the legacy by which he hoped to be remembered. By virtue of his royal position as well as his steady commissions, he was West's single most important patron. West's first commission for the king came from the royal librarian Richard Dalton for a painting entitled Cymon and Iphigenia (1762, location unknown), a subject drawn from Giovanni Boccaccio's Decameron.2 Although that painting apparently never reached the king's collection, West painted numerous paintings for George III, including portraits of the royal family and history paintings with themes from ancient, medieval, and modern history; Renaissance literature; and the Bible. West also painted a number of allegorical subjects to decorate Windsor Castle.

In 1768, West's first direct contact with the king was facilitated by another powerful patron, Robert Hay Drummond, archbishop of York.3 After seeing Agrippina Landing at Brundisium with the Ashes of Germanicus (1768, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Conn.), which West painted for the archbishop, George III ordered a painting of another classical theme-The Departure of Regulus from Rome (1769, The Royal Collection, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II). Over the next thirty years West would paint about sixty works for the king, for which he received upwards of thirty-four thousand pounds. Beginning in 1780, the king also paid West an annual stipend of one thousand pounds.4 That year West began to style himself as the "Historical Painter to the King of England," an epithet by which he is still celebrated.5

Analysis

Pharaoh and His Lost Host in the Red Sea represents an episode found in Exod. 14:26-28:

And the Lord said unto Moses, Stretch out thine hand over the sea, that the waters may come again upon the Egyptians, upon their chariots, and upon their horsemen.

And Moses stretched forth his hand over the sea, and the sea returned to his strength when the morning appeared; and the Egyptians fled against it; and the Lord overthrew the Egyptians in the midst of the sea.

And the waters returned, and covered the chariots, and the horsemen, and all the host of Pharaoh that came into the sea after them; there remained not so much as one of them.

This painting is one of at least sixty that West derived from the Old Testament and the Apocrypha.

|

|

| Figure 1. Infrared reflectogram detail of the exodus that appears in the center left portion of West's painting. |

Though West's romanticism might have been understood in the eighteenth century under the rubric of the sublime, an aesthetic category articulated by Edmund Burke in 1757, contemporary critics rejected the painter's new approach as radical and unfocused. In 1792 at the Royal Academy, West exhibited a larger version (150 x 120 inches) of Pharaoh and His Host Lost in the Red Sea (about 1792, location unknown), for which Worcester's painting is a study. At least two published responses agreed in their sharp criticism of the painting. The first critique appeared in the Morning Chronicle: "Though there may be those who will call violent and extravagant genius, wonderfully Sublime! the praise of such is not worthy the ambition of genius. In this great painting there is nothing which can properly be called principal; nothing for the eye to rest upon."7 The other critic was equally troubled that the painting lacked order, a quality that was typical of West's earlier neoclassical compositions: "If we had not the express assurance of the learned Painter himself, that the above is positively the subject of the picture, we should have pronounced it to be a very clear view of satanic confusion, tossing amid the fiery billows of Penal Hell."8 West was clearly testing the limits to which an artist could express chaos through carefully orchestrated disorder.

This painting is a study for one of a cycle of paintings that in 1779 George III commissioned West to create for the Royal Chapel at Windsor, a series the history painter called "the progress of Religion Revealed, from its commencement to its completion."9 The plan for the chapel decoration changed over the duration of the extremely protracted project. In 1779 West intended just sixteen paintings, but by 1816 he told John Quincy Adams that he planned thirty-six. Subjects were added and others were deleted from the plan, and the total number of separate themes begun by West reached at least forty-six. The original list of subjects for the chapel was drawn up by West in consultation with the king and was approved by Dr. Richard Hurd (1720-1808), later the bishop of Worcester, and Dr. John Douglas (1721-1807), the bishop of Salisbury and dean of Windsor.10 West exhibited many of the paintings and preliminary drawings for the chapel at the Royal Academy between 1781 and 1801, including the large-scale version of Pharaoh and His Host Lost in the Red Sea in 1792, as noted above. West was paid the substantial sum of 1050 pounds for the completed version of this painting.11

The chapel at Windsor was designed in the seventeenth century by Hugh May (1621-1684) and was originally decorated by Antonio Verrio (about 1639-1707). An early version of West's scheme for the wall decoration is recorded in a series of drawings apparently made about 1780 with the architect Sir William Chambers (1723-1796), whose design for the interior framed the paintings in neoclassical arches, pilasters, and other ornamentation. The original plan placed large, vertical images of New Testament themes under the arches, with smaller, horizontal Old Testament subjects above. Pharaoh and His Host Lost in the Red Sea was to have filled the small horizontal space that was second from the left end of one wall. A pen, wash, and watercolor drawing of the wall (about 1780, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Conn.) shows the painting's original source and placement.12 West based his early conception of the subject on a work by the French baroque history painter Nicolas Poussin, which West knew from an engraving in his own collection.13 Pharaoh would hang above a large Christ Healing the Sick (about 1780-81, location unknown).14 The small, horizontal painting to the left of Pharaoh was intended to be Moses and Aaron before Pharaoh (a later vertical version of this subject, painted in 1796, is at Bob Jones University, Greenville, S.C.).15 To the right, the center of the wall was to be occupied by The Ascension (about 1781-82, Bob Jones University, Greenville, S.C.).16

|

|

| Figure 2. Benjamin West, The Overthrow of Pharaoh and His Host, pen and sepia and sepia wash, 12 3/4 x 9 7/8 in. (32.4 x 25.1 cm), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, from the collection of John Hubbard Sturgis, born 1834, died 1888, given in his memory by his daughters, Miss Frances C. Sturgis, Miss Mabel R. Sturgis, Mrs. William Haynes-Smith (Alice Maud Sturgis), and Miss Evelyn R. Sturgis, 42.602. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Reproduced with permission. © 2000 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All Rights Reserved. |

A cursory drawing of the interior walls of the chapel (1801, Friends Historical Library, Swarthmore College, Swarthmore, Penn.) shows that the new version of Pharaoh and His Host Lost in the Red Sea was to be situated with two other paintings of Moses. West planned to place a large painting (216 x 147 inches), Moses Receiving the Laws (1784, Palace of Westminster, London), on the center of the wall.19 To the left West intended to install the large version of Worcester's painting and to the right Moses Showing the Brazen Serpent to the Israelites (about 1790, Bob Jones University, Greenville, S. C.).20 Above Pharaoh and His Host Lost in the Red Sea, West's annotation names a painting "12 Tribes/Joshua," perhaps a reference to Joshua Passing the River Jordan with the Ark of the Covenant (1800, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia).21 Below Pharaoh, West planned to display Noah Sacrificing (about 1801, San Antonio Museum of Art, Texas).22 The prior pairing of Old and New Testament themes on each wall had now given way to separate walls devoted to the two texts.

In 1796 George III named James Wyatt (1746-1813) in place of William Chambers as the architect at Windsor. Wyatt's conception of the chapel changed the design from a neoclassical to a neo-Gothic interior. Chambers' rounded arches were replaced with pointed arches. During Wyatt's tenure, West expanded the number of compositions for the chapel, perhaps because the new architect considered converting the larger Horn Court into the king's chapel. Despite this apparently productive start, in 1801 Wyatt brought news that the project was suspended, and West blamed him as a rival.23 West resumed work, first at the king's request and in 1803 at his own expense.24

It was probably during this period of late activity on the chapel paintings that West began reworking the composition of Pharaoh and His Host Lost in the Red Sea. The chariot wheel is inscribed with two dates, 1792 and 180[?].25 While the compositional changes discussed above were most likely made in 1792, West's retouching after 1800 probably included the addition of the figures in the upper right section (fig. 3). Whereas most of the figures in that group of Israelites have a clear underdrawing with color added on top, two heads were painted without an underdrawing. The woman to the left of the other two women huddled closely together with their children was added late in the work's development. Note that in the infrared detail her face appears transparent and has no linear structure because her head was painted on top of the veil that flowed from the now-central woman's head. Similarly, the elderly man above them to the right was added without a preliminary underdrawing. These additions create numerical symmetry among that block of figures—three men above, three women in the middle, and three children below.

![]()

Figure 3. Detail of the Israelites viewed with infrared reflectogram of Benjamin West, Pharaoh and His Host Lost in the Red Sea.

Despite West's more than twenty years of effort on the project, the Windsor chapel was never completed. The studies, including Pharaoh and His Host Lost in the Red Sea, apparently remained the property of West, as they were exhibited in 1821 in the gallery established in his house by his sons after his death. All but one of the completed paintings were given to West's sons in 1828 by George IV, and most were sold at auction in 1829.

Notes

1. Inventory of the estate of Joshua Babcock, April 9, 1783, Westerly Town Clerk's Office, Westerly, Rhode Island.

2. For Joshua Babcock's biography, see Dexter 1885, 293-94; Babcock 1903, 30-33; and Brown 1909, 15-17.

3. Newport Mercury, April 5, 1783.

4. Rhode Island Vital Records X, 1898, 437.

5. Rhode Island Vital Records, n.s., v. 11; Newport Burial Ground 1985, 45-46; "Descendants of Peter Bours," Redwood Library and Athenaeum, web site.

6. Newport Mercury, September 18, 1759; April 28, 1761; March 23, 1762; May 27, 1765; August 19, 1765.

7. Mason 1891.

8. Mason 1890, 168.

9. Recorded by Laura K. Mills, Common Burial Ground, Newport, R.I.

10. Stevens 1967, 95-107.

11. Dresser 1961, 36, 37-38.

12. Park 1919a, 75-78.

13. Steegman 1936, 309-15.

14. Ribeiro 1984, 144-57.

15. Paul Staiti dates the Bours portrait to about 1770 in Rebora 1995, 264.

16. Walpole, as quoted in Miles and Simon 1979, cat. no. 15, n.p.

17. Ribeiro 1995, 106.

18. Babcock 1903, 64-65.

19. Dr. Levi Wheaton, as quoted in Updike 1907, II, 49.

20. Updike 1907, I, 223.

21. Joshua Babcock estate inventory.

22. Rhode Island Vital Records X, 1898, 483 and XIX, 1910, 361; "Bours Family," typescript, object file, Worcester Art Museum.