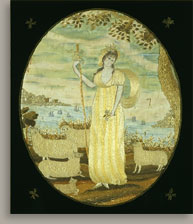

Description The farm nearest the viewer features a two-story, cream-colored house that is visible through a gap in the line of trees. To the right of that house, on a much smaller scale than the shepherdess, two figures—apparently women dressed in red and blue and wearing dark hats—face one another in conversation. The clearing they occupy extends to the right, where two more properties are delineated: in one stands a large, two-story, hip-roofed pink house with a white ornamental fence that extends back toward a barn. A yard to the left of the dwelling is enclosed by the side of the house and the white fence, the front of the barn, and an unpainted post-and-rail fence. A larger, adjoining pasture is enclosed by the unpainted fence on two sides and hedges on the other two sides. A tiny figure stands in the opening between this farm and the water. The adjacent property features another two-story, cream-colored house with a one-story pink structure adjoining it. Two sailing vessels are visible on the water near the houses. The one closest to the viewer carries three men and is powered by a single open sail. A long pennant waves from the top of the mast. A larger, two-sail vessel is anchored beyond the moving boat. Both crafts are reflected in the still water. A white post-and-rail fence, also reflected in the water, lines the left bank; parallel to it is a row of posts without rails. Beyond the two farms, fronted by partitioned fields, is a row of buildings representing a village. The central structure is a meetinghouse with a tall steeple. Those buildings are smaller in scale than the two houses near the water, and each structure in the village is painted gray and white. In the distance, where the land narrows to a slight triangle, is a collection of buildings painted cream and red; this settlement appears to include at least one warehouse and several docked sailing vessels. Three mountain peaks along the horizon reflect pink and white light. The sky is painted with white and gray horizontal brushstrokes and embellished with loosely painted white and gray cumulus clouds. This work is technically more sophisticated than most overmantel paintings. The artist has graded the light and dark areas of the foreground trees, the drapery on the shepherdess, and the sheep to convey their volume. Similarly, the sail on the foremost vessel varies from white along the top and right edges to dark gray in its concave, billowing surface. The artist also attempted to represent the reflections of the boats, trees, fences, and sky in the water. The drawing, however, is still rather elementary, and shifts in scale that were intended to suggest spatial recession are not really successful. The blue and green hues in the sky and water have faded to gray, and the paint layer is cracked overall. Biography The Baldwin overmantel was purchased by George Sumner (1824–1893), a native of Shrewsbury with an interest in historic preservation, in 1885, when the Baldwin house was razed. A Worcester businessman, antiquarian, and descendant of a prominent Shrewsbury family, Sumner installed the painting in the study of the family home built by his ancestor the Reverend Joseph Sumner.3 As a young man, George Sumner had worked in the Shrewsbury store run by Henry W. Baldwin.4 Sumner was elected a member of the Worcester Society of Antiquity in 1877 and served as vice-president from 1882 until his death in 1893. His antiquarian interests and his early employment by the Baldwin family account for his knowledge of the overmantel and interest in preserving it. Analysis The shepherdess theme, featured in the foreground of the Baldwin overmantel, was introduced to the American colonies through seventeenth- and eighteenth-century English and Dutch prints. By 1735, women’s needlework incorporated this theme, and such prominent rococo American artists as Joseph Blackburn and John Singleton Copley created portraits of sitters in shepherdess costume.7 The theme remained popular in embroidery, prints, and paintings until the end of the century. Pastoral subjects were especially popular in Boston, suggesting an interesting dynamic between urban sophistication and rural idealism.8 There is a similar tension in the Baldwin overmantel among the shepherdess and farms in the foreground, the rural village in the middle distance, and the larger commercial center in the background. Because Shrewsbury was a small village in central Massachusetts, the image probably resonated differently there than it would in a city such as Boston.

The overall composition and shepherdess may well have been derived from prints, but the house in the foreground apparently was based on an actual dwelling. Such contemporaneous paintings as Overmantel from the Reverend Joseph Wheeler House and Ralph Earl’s Looking East from Denny Hill demonstrate that late-eighteenth-century American landscapes often contained specific details of the homes they decorated. Although there are no photographs of the Baldwin house to indicate whether it is represented here, the distinct character of the foreground houses in the Baldwin landscape and in the two similar overmantels suggests that each painting features an actual house, almost certainly the one in which it originally hung over the fireplace. Notes 2. Baldwin 1881, 655. 3. Strickler-Harlow conversation, notes in object file, Worcester Art Museum. 4. Sumner 1895, 18. 5. Little 1972, 136. 6. Little 1984, 88. 7. Paul Staiti, "Ann Tyng," in Rebora 1995, 176–78. 8. For examples, see Bowen 1923, 70–73; Cabot 1941a, 28–31; idem, 1941b, 367–69; idem, 1950, 476–79; and Ring 1993, I, 17, 36–38, 89. 9. "Adelaide; or, The Lovely Rustick," Massachusetts Magazine 2, no. 4 (April 1790): [195]. |