Gilbert Stuart Gilbert StuartElizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury (Mrs. Stephen Salisbury I), 1810–11 Description Salisbury's blue-gray eyes are focused on the viewer. White highlights appear to the left of each large pupil. Her eyebrows are barely suggested by thin lines of brown and pink paint on top of a gray glaze. A white highlight runs the length of the nose. A shadow to the right of the nose suggests a light source in the upper left. Her lips and cheeks are very pink in contrast to her very pale forehead. Above her brow is an area of thicker ivory-colored opaque paint. The contour of her neck is outlined with a stroke of brown paint. Salisbury wears a high-waisted, short-sleeved light gray dress trimmed with pearls on the sleeves and bodice. The details in the gathered sleeves and bodice of the dress were loosely painted with strokes of black and gray paint. The shadow below the bodice was painted with loose, large strokes of black. A sheer kerchief with a high lace collar is tucked into the low-cut bodice of the dress and fastened with an oval brooch, which was hastily painted with quick, short strokes of red, dark gray, white, and ivory surrounded by tan paint suggestive of gold. Around the ring of tan paint are dots of opaque white paint representing pearls. The lace collar was painted with loose, short strokes of opaque white, gray, and black paint. The lace veil that drapes over the back of her head also covers her proper left side, but her proper right arm is left bare. More of the lace veil is visible on the arm of the chair in the left of the composition. Her proper right arm casts a shadow along the right side of her body. The lace on the veil is rendered very loosely with broad brushstrokes of opaque white and black to faintly suggest a floral pattern. No attempt was made to define the pattern of the lace on the veil near her hands; instead, the brushstrokes appear jagged and hastily painted. On the right side of her face, a faint and loosely painted black line from the lowest curl on her cheek to the veil suggests another fold in the fabric. Salisbury sits in an armchair of blond wood with solid upholstered panels of rose-colored fabric. The back of the chair is not visible. The sides of the chair are tapered toward the arm, and the ends are turned outward. The pink paint visible over the side of the chair in the left of the composition appears to be tassels or fabric from a pillow or cushion. The veil was painted over part of the upholstery on the right side of the chair, though it is apparent that Stuart added the dark brown outline of the chair's curved arm after hastily painting the lace veil draped over it. Stuart used thicker yellow paint for the highlights in the wood. The background of the portrait is olive and has visible brushstrokes. It is darker to the left of the sitter and only partially covered by the yellow paint used for the wood of the chair's right arm. Biography Stephen Salisbury I was the youngest of eleven children born to Martha Saunders (1704–1792), of Boston, and Nicholas Salisbury (1697–1748). When he turned twenty-one in 1767, Samuel, who was seven years older, took him in as a partner in his business on the condition that Stephen would open a branch of their Boston store in Worcester. The firm soon prospered in the country town, and Stephen settled permanently in Worcester in a mansion he built on Main Street. He was joined by his widowed mother, Martha, his unmarried sister Sarah, and his brother Samuel and his family for eight years during the Revolution, and Martha Salisbury remained with Stephen until her death in 1792. Almost twenty-nine, Elizabeth Tuckerman was twenty-one years younger than her fifty-year-old fiance in early January 1797. Her upcoming arrival in Worcester led Stephen to make the interior of the mansion suitable for his bride. In the weeks preceding their marriage, Stephen was busy orchestrating the arrival of wagon loads of her belongings. After one shipment arrived, Stephen wrote to his betrothed, "1 Dining Table 1 Pembrook Table 2 Card Tables 1 Stand Table 2 fire Screens and 6 Chairs of your furniture, all in good order excepting the dining table which was occasioned by a nail among the shavings that came round it . . . the Injury can be easyly repaird."5 Stephen sent her measurements for the amount of carpeting needed to cover the stairs and instructions to purchase new looking glasses that were "more Suitable and Agreeable to you."6 These additions and others must have produced satisfactory results, for when Elizabeth's siblings visited her in Worcester after her marriage, they were impressed. Elizabeth's mother wrote from Boston, "Your sister gives me a most agreeable account of your situation, says you live in stile, likes your husband very much indeed. My dear I think you must be very happy."7 Elizabeth Tuckerman married Stephen Salisbury on January 31, 1797 at the Hollis Street Church in Boston, where she had been admitted as a member in February 1796.8 Stephen and Elizabeth had three children, but only their eldest, Stephen Salisbury II, born on March 8, 1798, survived childhood. Their daughter, Elizabeth Tuckerman, was born on March 9, 1800, and died on December 27, 1803; their son, Edward Tuckerman, was born May 7, 1803, and died on August 25, 1809.9 Elizabeth and Stephen Salisbury also cared for her orphaned niece, Eliza Tuckerman Wier (1795–1819). Eliza later married John Hubbard, who died in 1825, and their orphaned daughter, Elizabeth Lucretia Wier Hubbard (1819–1841), was adopted by the Salisburys.10 The latter part of Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury's life is discussed in the biography section of Chester Harding's Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury (Mrs. Stephen Salisbury I). Analysis After her marriage, Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury's connections to her Boston siblings remained strong through frequent correspondence and visits. Her brother Joseph was the first of her siblings to sit for Stuart. In a January 1809 letter Joseph made excuses to Elizabeth for not writing earlier: "But besides my usual occupations, I lose a considerate part of two days in each week, in sitting for my picture. Stewart is painting me. Are you surprised at this? Economy will do much, my dear Sister. It has saved from the income of the past year $200; & to gratify my Sarah, to whom I am wholly indebted for this extraordinary sum, I am expending 100 of it for a portrait."14 Joseph Tuckerman did not use the remaining hundred dollar surplus, however, to commission Stuart to paint a portrait of his second wife, Sarah Gray Cary (1783–1838), whom he married in 1808.15 Joseph Tuckerman, a bust-length portrait (1809, private collection), represents the thirty-one year-old paster of a Unitarian congregation in Chelsea in his clerical robes. Whether she was surprised or not, Elizabeth became the second of her siblings to sit for Stuart.16 Stephen Salisbury did not sit to Stuart until 1823, but he encouraged his wife to have her portrait painted in June 1810. Salisbury wrote from Worcester to Elizabeth, who was in Boston with their son, Stephen II, "Hope you will not fail calling on Steward this morning should the Portrait he takes, be not halve so handsome and pleasant as the original, I certainly shall not like it."17 Although Elizabeth's correspondence mentions visiting family members, she did not refer to her Stuart portrait sittings in family letters. It is very likely that she was able to sit for Stuart in June or early July 1810. By the end of August, Stephen and Elizabeth Salisbury wrote their Boston nephew Josiah Salisbury (1781–1826) for an update on Stuart's progress with the portrait. Josiah informed Stephen, "—I have called at Stewarts but could not get a sight of the picture."18 The Salisburys turned next to Elizabeth's brother Joseph for assistance, but he did not have much better news to report after visiting Stuart:

As with Elizabeth, no references for Samuel sitting for Stuart have been found. It does not appear that Elizabeth and Samuel sat for Stuart together, but judging from the copy of the receipt, his sitting was likely during the same year. After paying Stuart for the two portraits, Stephen Salisbury did not receive them. By early February 1811, when Stephen was in Boston visiting Samuel, the portraits were still with Stuart. Stephen wrote home to Elizabeth that he "would go and see her likeness at Stewards—Steward says it would not due to Varnish the Pictures until the Snow is gone, so that he don't intend we shall have them until the Spring—"21 Elizabeth replied, "I am glad you went to Stewarts, but you do not say whether you are as well pleased with my likeness as ever."22 At the end of April, after visiting Stuart, Samuel's son Josiah wrote to inform Stephen and Elizabeth that Stuart had said the portraits were finished and ready to be delivered. He offered his assistance in forwarding them,23 but his announcement turned out to be premature. Samuel wrote on May 8 that "I saw Stewart on Monday he said the Pictures were not Varnish'd but he would do them directly if ready they shall be sent up by Howard—"24 The portraits were not sent, and an exasperated Josiah wrote to his uncle on May 11: "Have been endeavoring to get the pictures from Stewart's. very little dependence can be placed upon anything he says. When I first called upon him, he assured me without hesitation, that they were completed, & ready for delivery—& yet, it afterwards appeared, that they were not varnished.—I Shall attend to it & as soon as they are actually finished, Mr. White shall make a Case for them."25 Josiah's next letter to Worcester, sent three days later, explained that Stuart's wife said the artist was ill and unable to answer any questions. Whether Stuart was actually ill or had run out of excuses, the Salisburys waited about a month longer for the portraits. A letter from Josiah of May 30 skeptically announced that Stuart claimed to have finished the portraits, but the news was apparently true, since on June 18, 1811 the two portraits were finally packed and sent to Worcester.26

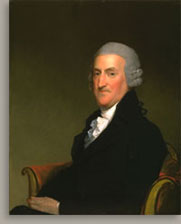

The portraits Stephen Salisbury commissioned of his wife and brother function as companion portraits, but it appears that Stephen chose to frame them differently.29 Both portraits are on mahogany panel and have similar dimensions. Samuel and Elizabeth are both seated and turned toward each other. The backgrounds of their portraits are the same olive color. The chair in their portraits, which appears with variations in many other Stuart portraits, is likely a studio chair or product of Stuart's imagination. Samuel's chair shows a low curved back, and it is upholstered in a brighter red fabric than that in Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury (Mrs. Stephen Salisbury I). According to Thomas Michie, curator of decorative art at the Rhode Island School of Design's Museum of Art, these chairs resemble an English or American version of the French bergère-type armchair.30 This unusual chair is often shown with fancier gilded arms, with and without a low or high rounded back, and upholstered in rose, red, green, or black.31 Sally Foster Otis (Mrs. Harrison Gray Otis) (1809, Reynolda House, Winston-Salem, North Carolina), Hepzibah Clark Swan (Mrs. James Swan) (about 1806–10, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), and Adam Babcock (about 1806–10, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) are just a few examples of Stuart portraits of Boston sitters painted about the same time as the Salisburys, who are represented in this chair. Stephen mentioned the portrait Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury in a letter to Elizabeth, who was in Boston, on October 30, 1811. He informed her of all the improvements he had made to their house in her absence. Included in the lengthy list was having her "Picture fraim new Gilt," and he added words he knew she would want to hear: "You know I love your very picture—"32 Notes 2. Oliver and Peabody 1982, 556. 3. Salisbury 1885, I, 75, and Roberts II, 1897, 324. Josiah wrote to his uncle Stephen, "I expect to live with Phillips the next year as Tuckerman intends to go into College." Josiah Salisbury, Cambridge, to Stephen Salisbury, Worcester, March 28, 1796, Salisbury Family Papers, Manuscripts and Archives, Sterling Memorial Library, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., series III, box 12, folder 110. 4. Edward Tuckerman, Jr., Boston, to Stephen Salisbury I, Worcester, September 8, 1794, Salisbury Family Papers, American Antiquarian Society (hereafter cited as SFP, AAS), Worcester, Mass., box 8, folder 2. 5. Stephen Salisbury I, Worcester, to Elizabeth Tuckerman, Boston, January 2, 1797, SFP, AAS, box 9, folder 2. 6. Ibid. 7. Elizabeth Tuckerman, Boston, to Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, Worcester, March 22, 1797, in ibid. 8. Hollis Street Church, Boston, Records of Admissions, Baptisms, Marriages, and Deaths, 1732–1887, New England Historic and Genealogical Society, Boston, MSS 293a, folder 6, 418. 9. Salisbury 1885, I, 35. 10. Eliza Tuckerman Wier was the daughter of Elizabeth's sister Lucretia (1770–1797) and her husband Robert Wier (d. 1804). Elizabeth Lucretia Wier Hubbard married Reverend J. Erskine Edwards and died in Stonington, Connecticut. Her remains were interred in the Salisbury family plot in Rural Cemetery in Worcester. Massachusetts Spy (Worcester), June 2, 1841. 11. Stephen Salisbury I, Worcester, to Elizabeth Tuckerman, Boston, January 9, 1797, SFP, AAS, box 9, folder 2. 12. This portrait was previously attributed to Christian Gullager in Forbes 1930a, 7, 10, but the artist is now listed as unknown. The condition of the painting limits further study. Other artists must be considered, including Jeremiah Stiles (1771–1826), who was also known to have painted Elizabeth Salisbury. Joseph Tuckerman wrote to Elizabeth, "When I visit you in the spring, I shall have Stiles retouch that which he painted, & take it from him. It will not look so well as Stewart; but it will do." Joseph Tuckerman, Chelsea, to Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, Worcester, January 23, 1809, SFP, AAS, box 14, folder 3. 13. The miniatures of Stephen Salisbury I and Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury were likely painted by William Lovett in 1798. Unfortunately, they were stolen from the museum in 1944. For reproductions see Strickler 1989, 91. Stephen's hair, neck cloth, and shirt ruffle are similar in the Gullager portrait and the miniature. The wrapping gown, head wrap, hairstyle, and cleft chin in the Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury by the unidentified artist are repeated in the miniature. 14. Joseph Tuckerman, Chelsea, to Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, Boston, January 23, 1809, SFP, AAS, box 14, folder 3. 15. Joseph Tuckerman's first wife was Abigail Parkman (1779–1807). Her parents sat for Stuart, and her father, Samuel Parkman (1751–1824), commissioned Stuart to paint Washington at Dorchester Heights (1806, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), which he presented to Boston to be hung in Faneuil Hall. McLanathan 1986, 128–31, and McKusick 1958, 42–43. For the Parkman portraits by Stuart see Park, II, 570–73, cat. nos. 608–12. 16. Edward Tuckerman III was the third sibling who sat for Stuart. Edward's first wife, Hannah Parkman (1777–1814), was the sister of his brother Joseph's first wife, Abigail Parkman. Stuart painted Edward, Hannah Parkman, and two portraits of Edward's second wife, Sophia May (1784–1870). Tuckerman 1914, 60, and Park 1926, II, 768–70, cat. nos. 855–58; IV, 534–36. One of the Stuart portraits of Sophia May Tuckerman is in a private collection; the others are currently unlocated. 17. Stephen Salisbury I, Worcester, to Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, Boston, June 15–16, 1810, SFP, AAS, box 14, folder 5. 18. Josiah Salisbury, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury I, Worcester, August 28, 1810, SFP, AAS, box 14, folder 6. 19. Joseph Tuckerman, Chelsea, to Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, September 28, 1810, Worcester, in ibid. 20. Copy of Stuart's receipt to Stephen Salisbury I, November 8, 1810, in the hand of Stephen Salisbury III, SFP, AAS, box 15, folder 3. 21. Stephen Salisbury I, Boston, to Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, Worcester, February 11, 1811, SFP, AAS, box 15, folder 1. The week before, Stephen had written Elizabeth to inform her that he had not had a chance to go see Stuart. Stephen Salisbury I, Boston, to Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, Worcester, February 4, 1811, in ibid. 22. Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, Worcester, to Stephen Salisbury I, Boston, February 13, 1811, SFP, AAS, box 15, folder 2. 23. Josiah Salisbury, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury I, Worcester, April 30, 1811, in ibid. 24. Samuel Salisbury, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury, Worcester, May 8, 1811, in ibid. 25. Josiah Salisbury, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury I, Worcester, May 11, 1811, in ibid. 26. Samuel Salisbury, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury, Worcester, June 18, 1811, in ibid. 27. Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, Worcester, to Henry Harris Tuckerman, Boston, January 26, 1809, SFP, AAS, box 14, folder 3. Over the course of their marriage, Stephen Salisbury always indulged her wishes. When Elizabeth was in Boston in 1817, she wrote home apologetically, "I had no idea that I should spend all the money you gave me, but the fact is, that articles of female dress are very expensive, and the money goes, I will not say I don't know how, for I can show, but very fast." Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury I, Worcester, June 12, 1817, SFP, AAS, box 17, folder 5. Stephen reassured her, "I need not repeat to you My sincere wish that you would purchase for yourself Laces or any other articles for dress that you have a fancy for." Stephen Salisbury I, Worcester, to Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, Boston, June 12, 1817, in ibid. 28. Veils are seen in numerous other Boston portraits, including Elizabeth Temple Winthrop (Mrs. Thomas Lindall Winthrop) (1806, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston), Hepzibah Clark Swan (Mrs. James Swan) (1808, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), Hannah Parkman Tuckerman (Mrs. Edward Tuckerman (unlocated), and Sarah Wentworth Apthorp Morton (Mrs. Perez Morton). For their fashionableness see Lester and Oerke 1940, 68. 29. Stephen Salisbury, Worcester, to Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, Boston, October 30, 1811, SFP, AAS, box 15, folder 3. 30. Thomas S. Michie, Curator of Decorative Arts, Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, to Laura Mills, May 6, 1998, Worcester Art Museum curatorial files. See examples in Montgomery 1966, 175–77. 31. DeLorme 1976, 127. 32. Stephen Salisbury, Worcester, to Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, Boston, October 30, 1811, SFP, AAS, box 15, folder 3. |