| Gilbert Stuart Born North Kingston, R.I., December 3, 1755. Died Boston, Mass., July 9, 1828. Gilbert Stuart was America's leading portraitist of the Federal period, and he set a standard for portraiture that would continue even after his death in 1828.1 After training in London with the American artist Benjamin West and achieving success in the tight London portrait market and in Ireland, Stuart won acclaim in New York, Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., and finally Boston. Best known for his portraits of George Washington, Stuart painted more than a thousand portraits of the next four presidents of the United States, governors, diplomats, merchants, military heroes, judges, ministers, college presidents, and other leaders of the new nation as well as their wives and children. With his sophisticated technique and knowledge of the latest London styles, Stuart sought to make an artistic statement using decorative brushwork and glowing colors. He belonged to a new class of professional portrait painters that wanted to create more than just a flattering representation of a sitter. As the Boston poet Sarah Wentworth Morton wrote about Stuart's portraits in 1803, "'Tis character that breathes, 'tis soul that twines / Round the rich canvas, trac'd in living lines."2 Another sitter declared that a Stuart portrait "was very desirable" and remained the standard of comparison.3 "It will not look as well as Stuart but it will do," stated a Boston man about a portrait by another artist.4 Even other artists compared their work with Stuart's. Charles Willson Peale reminded his son Rembrandt Peale (1778–1860) in 1805, "I hope you will by a little more practice please the ladies equally well if not better than Stewart."5 Stuart was the youngest of three children born to the Scottish snuff maker Gilbert Stuart and Elizabeth Anthony. After arriving in this country, the elder Stuart built and operated a snuff mill in North Kingston, Rhode Island. The artist was baptized as Gilbert Stewart at St. Paul's Church, Narragansett. When he was a young boy, Stuart's family moved to Newport, Rhode Island, where the artist's father ran a shop at the north corner of Banister's Row. Here, as noted in an advertisement published in the Newport Mercury, he "Continues to Make and Sell, Superfine Flour of Mustard," as well as other goods.6 Stuart's early artistic inclinations have been frequently discussed. In 1769 he met Cosmo Alexander (ca. 1724–1772), an Italian-trained Scottish artist who was visiting Newport.7 One of Alexander's patrons, Dr. William Hunter, introduced him to the young Stuart. According to family tradition, Dr. Hunter had recognized and encouraged Stuart's talent and around 1765 commissioned the boy to paint a portrait of his spaniels (Hunter House, Newport, Rhode Island). Alexander gave Stuart art lessons and employed him as an assistant. In 1770 Stuart accompanied Alexander on a painting tour that included stops in Philadelphia, Delaware, and Virginia before their voyage to Edinburgh. Alexander died unexpectedly on August 25, 1772, leaving the seventeen-year-old Stuart stranded in Edinburgh. He worked as a crew member on a collier bound for Nova Scotia and eventually arrived home in Newport, where he continued to paint portraits.8 The influence of Cosmo Alexander as well as some reliance on English portrait mezzotints is apparent in Stuart's early Newport works. For instance, Stuart's double portrait Mrs. John Banister and Her Son (about 1773, Redwood Library and Athenaeum, Newport, Rhode Island) shows a debt to Alexander's earlier double portrait Deborah Malbone Hunter and Her Daughter Eliza (1769, Preservation Society of Newport County, Newport, Rhode Island). The formulaic rendering of the facial features and the compositions are similar in both portraits: the seated mother turned three-quarters left is represented with her arm around her standing child. Stuart, however, added a small dog between the figures, a device that allowed him to avoid painting hands. The boy's large head and the mother's unnaturally thin and elongated upper body also reveal Stuart's inexperience. Stuart's emphasis on outline in Mrs. John Banister and Her Son is very different from his later practice of building up the composition with fluid strokes of color. The costume of his sitters is more crudely rendered than Alexander's; Mrs. Banister's loose, uncorseted dress and blue ermine-trimmed robe were likely borrowed from a mezzotint, a practice employed by other colonial artists in New England and the southern colonies, including John Wollaston, with his Ann Gibbes (Mrs. Edward Thomas), and John Singleton Copley.9

Stuart's loyalist father decided to move his family to Nova Scotia in the summer of 1775, and although a patriot himself, the artist departed for London on September 8, 1775. He struggled on his own, painting when he received commissions and working as an organist. Competition in the London portrait market was fierce and required more than just the ability to paint a likeness. Successful portraitists had studios in good neighborhoods to attract wealthy clients, dressed well, and charmed their sitters with witty conversation.11 Benjamin Waterhouse, Stuart's childhood friend, returned to London in 1776 after studying medicine in Edinburgh and tried to assist him in finding commissions. Around 1777 the destitute and desperate Stuart humbly wrote to Benjamin West, the history painter to King George III, who took him in as an assistant and gave him some instruction. As Stuart told later told the Kentucky artist Matthew Jouett (1787–1827), he was "allowd half a guinea a week for paint[ing] draperies & finishing up Wests portraits."12 In 1777 Stuart exhibited a portrait at the annual exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts in London for the first time.13

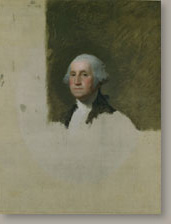

Stuart's success came at the age of twenty-six with the exhibition of The Skater (Portrait of William Grant) (1782, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.) at the Royal Academy, and it encouraged him to leave West's studio and work independently. His highly original composition represents Grant skating on the Serpentine River, with his arms confidently crossed and his feet in a graceful glide.14 On May 10, 1786, Stuart married Charlotte Coates (d. 1845), the sister of Dr. William Coates, a surgeon in the Royal Navy, whom Stuart had met earlier at an anatomy lecture. Gilbert and Charlotte would have five sons and seven daughters. According to daughter Jane, Charlotte's family initially did not approve of the marriage because of Stuart's "reckless habits."15 Although Stuart was busy painting portraits of prominent people, including the actress Sarah Siddons (1787, National Portrait Gallery, London) and a group of artists and engravers for the gallery of the London print seller John Boydell, he was extravagant and spent more than he earned. Jane Stuart attributed her father's problems to his lack of business sense but also defended him. She wrote "the manner in which he lived should not be called extravagant, as his employment warranted the outlay; his distinction as an artist entitled him to it; the class of persons he painted for required it."16 Still enjoying popularity, Stuart abruptly left London in the fall of 1787 to escape his creditors and went to Ireland, where his debts mounted again. Leaving his unfinished portraits and debts behind in Ireland five years later, Stuart and his family arrived in New York in May 1793. There, he immediately received commissions from prominent merchants, politicians, and Revolutionary War veterans.17 In November 1794, Stuart wrote to his uncle and benefactor, Joseph Anthony (1738–1798), about his reasons for visiting Philadelphia: "The object of my journey is only to secure a picture of the President & finish yours."18 With a letter of introduction from Chief Justice John Jay, Stuart secured a sitting from the president in Philadelphia in the spring of 1795, which resulted in a portrait that he copied about twelve times. Like most artists, Stuart recognized the potential for profits from replicas of portraits of Washington, and among his records was a memorandum dated April 20, 1795, that listed thirty-two commissions for replicas of the president's portrait.19

Stuart was greatly disappointed when the English engraver James Heath published a print of his "Lansdowne" portrait in January 1800 without his permission, and for the rest of his life he worried about other painters and engravers copying his likeness of Washington. In an attempt to discredit Heath's print, Stuart expressed in the Philadelphia Aurora on June 12, 1800, his "mortification" about Heath's engraving and announced that an engraving, intended for the "legislators of Massachusetts and Rhode Island," would be done from another of his full-length portraits of Washington: Stuart's proposed print was never realized, and unauthorized copies of his Washington portraits continued to be made. The Philadelphia merchant John E. Sword imported a copy of Stuart's Athenaeum portrait of Washington into Canton, China, to be reproduced in a painting on glass. Sword had promised Stuart he would not make copies but in fact planned to do a series of a hundred reverse-glass paintings of Stuart's Washington, to be sold in Philadelphia. The infuriated Stuart took Sword to court and won in 1802.23 Other cases followed in similar track. In 1806, when Samuel Parkman proposed to give an unauthorized copy of a Stuart portrait of Washington by William Winstanley to the city of Boston for Faneuil Hall, public protests ensued, and Stuart was persuaded to paint Washington at Dorchester Heights (1806, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston).24 Stuart still received requests for Washington portraits at the end of his life, but by then he was extremely circumspect. On March 6, 1826, he told Edward Everett (1794–1865), a United States congressman, he would paint another full-length portrait of Washington if he regained his strength and was "protected in the exclusive benefit of copies of it by engraving & otherwise for 14 years—I make this last condition with feelings injured by the repeated attempt by others to copy my works—to which I have devoted so much time & expense, not only without renumeration but without my consent."25 Imitation was not the kind of flattery Stuart sought, but he was not averse to it in other forms. His portraits received praise in the popular Philadelphia journal The Port Folio on June 18, 1803, when he exchanged verses with the Boston poet Sarah Wentworth Morton, who had sat for him on a visit to Philadelphia. In her poem "To Mr. Stuart, On His Portrait of Mrs. M," Morton flattered the artist:

Philadelphians certainly shared Morton's opinion and flocked to Stuart's studio at Fifth and Chestnut Streets and later outside the city of Germantown. After spending nine years in Philadelphia, Stuart went briefly to Washington, D.C., the new capital, in 1803, where his sitters included James and Dolly Madison and Thomas Jefferson. Stuart left Washington for Boston in July 1805 and remained there for the rest of his life.27 Stuart's career lasted more than fifty years, and he never lacked for sitters, even though he was notorious for not finishing commissions after the initial sittings had occurred. Mary Tyler Peabody Mann wrote to a friend in 1825, "At Stewart's room I saw a portrait of Webster, Mr. Quincy, President Adams and lady, Bishop Griswold, Mr. Taylor, &c. They were all unfinished."28 Mann's praise for Stuart's portraits even though they were unfinished is not surprising, because the artist had the ability to capture a sitter's personality by depicting only his or her head, as in Washington Allston (about 1820, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). Initial sittings to establish the head were typically done quickly. Stuart's Horace Binney (1800, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.), for example, required only two sittings, and according to the sitter, Stuart painted his hands, a large law book, and a coat "from an image in his thoughts." Binney stated that he never wore a mauve colored coat like the one Stuart painted him in, but that "he [Stuart] thought it would suit the complexion."29 Stuart's patrons were undaunted by his well-known delays in finishing portraits. Stephen Salisbury commissioned a portrait of himself from Stuart in July 1823, despite having waited about a year for Stuart to finally deliver portraits of his wife and brother that he had commissioned in 1810. The second commission was no different from the first two: Salisbury sent family members to Stuart's studio and received false promises and excuses for the delays.30 Other sitters were not as lucky as Salisbury and waited much longer. Twenty years after sitting for Stuart for the first time, an exasperated Thomas Jefferson was still trying to obtain his portrait from the artist.31 In response to an inquiry about Stuart by her nephew, the artist Mather Brown (1761–1831), Catherine Byles wrote, "We are told he is one of the best painters in the world & excels in his likeness; he has taken a number of portraits, his price is a hundred dollars; he is indeed very excentrick, he loves a cheerful bottle and does no work in the afternoon; he is very dilatory in finishing his pictures."32 But sitting for Stuart was an event, and his portraits were worth the wait. The wit and charm with which he entertained his sitters and visitors to his studio were legendary.33 With the exception of a few New York portraits, Stuart's style in America changed little from that which he had developed in England, though the degree to which he paid attention to details varied. His grand companion portraits of Matilda Stoughton de Jáudenes y Nebot and Don Josef de Jáudenes y Nebot (1794, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), for example, are more tightly painted than that of another New York sitter, Margaret de Long Izard Manigault (1794, Albright-Knox Gallery of Art, Buffalo, New York), whose dress is broadly painted with large, prominent brushstrokes. Stuart's attention to the elaborate costume and jewelry of the Jáudenesess suggests his ability to paint detail-oriented portraits when he desired to do so, which was not very often. Similarly, his rendering of the hands of Richard Yates (1793, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.) is unusual for an artist who typically painted hands in a cursory fashion. In Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury (Mrs. Stephen Salisbury I), for example, only a few strokes of brown paint outline the sitter's fingers, just as well-placed dots of flesh-colored paint indicate her knuckles and finger joints. More often than not, Stuart placed his emphasis on the sitter's head rather than on costume and background.

Stuart painted few full-length portraits, and their craftsmanship varied: The Skater (Portrait of William Grant) succeeded with ease and grace, whereas George Washington (Lansdowne Portrait), based on a well-known engraving of Bishop Bossuet by Pierre-Imbert Drevet after Hyacinthe Rigaud (1723, British Museum, London) is awkward. Washington, positioned with both feet turned out, appears short and stocky. Stuart must have recognized these flaws, because they were corrected in his full-length George Washington (Munro-Lenox Portrait) (1800, New York Public Library). Stuart preferred English twill canvases with a diagonal weave, as seen in Stephen Salisbury I, but he also painted on mahogany panels. While the difficulty of importing English canvas during the Embargo Act of 1807 and the War of 1812 may have led Stuart to resort to panels, this is not likely the reason because he actually began using them around 1800 in Philadelphia.34 A more plausible explanation for Stuart's use of panel is found in a letter by Oliver Wolcott, Jr., regarding his commission of a Washington portrait for the state of Connecticut: "Mr. Stewart observes, that the heat of our Climate will destroy Canvas, exposed in a public building, in about Twenty years & he recommends Mahogany Pannells, in lieu of Canvass. He says that the Pannells can be so constructed as not to warp or crack."35 In some cases these panels were scored to imitate the surface of the twill canvas. Whether he was using canvas or a scored panel, his dashing brushwork was further enlivened by the rough, textured pattern of his painting surface. Some of his panels, however, were smooth and not scored, as in Elisabeth Bender Greenough (Mrs. David Greenough). Shortly after Stuart's death, Washington Allston wrote a tribute to him in the Boston Daily Advertiser on July 22, 1828 and mentioned "his generous bearing towards his professional brethren. . . . To the younger artists he was uniformly kind and indulgent, and most liberal of his advice." 36Such younger assistants and students included his own children, Charles Gilbert Stuart (1787–1813) and Jane Stuart (1812–1888), and his nephew Gilbert Stuart Newton (1794–1835), the son of his sister.37 In Boston, John Ritto Penniman, who named a son after the artist, grinded colors for Stuart and borrowed books from him.38 At the end of July 1807, Thomas Sully spent three weeks in Boston with Stuart and claimed the instructions he received were "worth gold to me."39 Matthew Jouett spent four months studying with Stuart in 1816 and recorded his conversations with the artist.40 Samuel F. B. Morse (1791–1872) acquired a copy of Jouett's notes on Stuart's technique and attempted to imitate his handling of paint.41 Many other artists, such as Jacob Eichholtz (1776–1842), John Neagle (1796–1865), Sarah Goodridge (1788–1853), and James Frothingham sought Stuart's advice.42 Frothingham's Jonathan Brooks and Elizabeth Albree Brooks (Mrs. Jonathan Brooks) reflect his mastery of Stuart's bust-length portrait format, with its focus on the head. Gilbert Stuart died intestate and insolvent in Boston on July 9, 1828, and he was interred the following day in tomb number sixty-one in the Central Burying Ground, south of the Boston Common. The cost of Stuart's coffin and the undertaker's bill was only thirty-six dollars, a sum that suggests his coffin was wood and inexpensive. The artist's debts amounted to more than seventeen hundred dollars. John Doggett & Co., the art dealer and framemaker, filed a claim against Stuart for $326, but most of the other claims were for rent, wood, food, clothes, and other household provisions. An inventory of his estate by an unknown appraiser was filed and valued at only $375. It included an organ valued at $100 as well as books, prints, a silver snuff box, and "8 unfinished sketches of heads" in the front chamber with his easel. Whether Stuart's unfinished portraits of George (fig. 3) and Martha Washington, which were eventually sold and presented to the Boston Athenaeum for fifteen hundred dollars, may have been among the "8 unfinished sketches of heads" and thus undervalued remains a mystery, as does the question as to why they were not listed separately in the inventory. Less than two months after his death, the Boston Athenaeum, which had declared Stuart a life member in 1823, mounted a memorial exhibition of his portraits from August 4 until September 1, 1828, for the benefit of his widow and four daughters. Almost 250 Stuart portraits, many of Bostonians, were loaned for the exhibition, demonstrating Boston's high regard for the artist.43 Notes 2. Sarah Wentworth Morton, "To Mr. Stuart, On His Portrait of Mrs. M," quoted in Saunter 1803. 3. Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury II, Worcester, July 9, 1823, Salisbury Family Papers, American Antiquarian Society (hereafter cited as SFP, AAS), Worcester, Mass., box 21, folder 2. 4. Joseph Tuckerman, Chelsea, to Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, Worcester, July 9, 1823, SFP, AAS, box 14, folder 3. Fourteen years later, when Chester Harding painted portraits of some of the Tuckermans in 1823, Elizabeth's sister-in-law reported, "I like them much; my husband thinks them excellent, but that Stuart would have made them handsomer pictures." Jane Francis Tuckerman, Boston, to Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, Worcester, April 10, 1823, SFP, AAS, box 21, folder 1. 5. Charles Willson Peale, Carpoint, Maryland, to Rembrandt Peale, Philadelphia, May 8, 1805, quoted in Miller 1988, II, pt. 2, 829–31. Rembrandt Peale later claimed his George Washington (Porthole Portrait) (1824, United States Senate, Washington, D.C.) was more accurate than Stuart's popular and accepted George Washington (Athenaeum Portrait) (fig. 3). Verheyen 1989. 6. Miller 1933, 89; Stuart 1877, 641; Newport Mercury, November 17–24, 1766. 7. Dunlap 1918, I, 192–263. 8. McLanathan 1986, 19–21, and Goodfellow 1963, 317. 9. Miles 1995, 42. See also Copley's pastel portrait Mrs. Gawen Brown (1763, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston), which is based on Thomas Fry's engraving Maria, Countess of Coventry, illustrated in Fales 1995, 10, 11. 10. Evans 1999, 8–10. 11. For Stuart's departure for England see Evans 1999, 11. His mother petitioned the General Assembly of Rhode Island to join his father in Nova Scotia in February 1776. Rhode Island Records VII, 1862, 461–62. For the London portrait market see Pointon 1984. 12. Matthew Jouett's record of Stuart's conversation, quoted in Morgan 1939, 87. For Stuart in England see also McLanathan 1986, 35; Evans 1980, 52–59; and Evans 1999, 11–13. 13. Graves VIII, 1972, 295–96. For the praise some of his portraits received in the press, see Sawitzky 1932, 16, and Evans 1999, 21. 14. Pressly 1986, and Miles 1995, 162–69. 15. Stuart, 1877, 644, and McLanathan1986, 56. For the Stuart's children, see Evans 1999, 152–53, n. 11. 16. Stuart 1877, 645. 17. Evans 1999, 48, 53. For Stuart's Ireland portraits, see Sawitzky 1933a. 18. Gilbert Stuart, New York, to Joseph Anthony, Sr., Philadelphia, November 2, 1794, Photostats (1786–1800), Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston. 19. For Stuart's memorandum, "A list of gentlemen who are to have copies of the Portrait of the President of the United States," see Stuart 1876, 369, 373. 20. For the Vaughan portrait of Washington, see Miles 1995, 201–6. Dorinda Evans believes that X rays of the National Gallery's Vaughan portrait show evidence of Stuart's revision. Evans 1999, 140–41, nn. 3, 4. Oliver Wolcott, Jr., wrote in 1800 that the demand for replicas of Stuart's Washington portraits was increasing. Miles 1997, 120. 21. For more on Stuart's Washington portraits, see also McLanathan 1986, 78–96, and Evans 1999, chap. 4, 60–73. 22. Aurora (Philadelphia), quoted in Prime 1932, II, 35. For Stuart's unsuccessful proposed print see Stuart 1876, 369–70, and Evans 1999, 71. 23. Richardson 1970, and Evans 1999, 86. 24. Stuart 1876, 372, and McLanathan 1986, 129–31. 25. Gilbert Stuart, Boston, to Edward Everett, March 6, 1826, Edward Everett Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, P–349, reel 2. 26. Sarah Wentworth Morton, "To Mr. Stuart, On His Portrait of Mrs. M," quoted in Saunter 1803. 27. For Stuart's residences in Boston, see Swan 1936. For the possibility that Stuart visited Boston in 1774 or 1775 see Evans 1999, 10. 28. She continued, "We did not see Stewart—he is too far gone to appear anymore—and he paints very diligently now for he has an idea that he shall not live long." Mary Tyler Peabody Mann, Brookline, to Miss Rawlins Pickman, Salem, January 27, 1825, Horace Mann Papers II, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, reel 37. 29. Binney's recollections of sitting for Stuart were recorded by his nephew in 1852. Quoted in Miles 1995, 219–21. 30. After six months, Salisbury had his nephew deliver a note to Stuart. Stephen Salisbury I, Worcester, to Gilbert Stuart, Boston, January 6, 1824, SFP, AAS, box 21, folder 4. 31. Thomas Jefferson to Bernard Peyton, August 14, 1820, Thomas Jefferson Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, P–060, reel 10. For the Stuart portraits of Jefferson, see Meschutt 1981. 32. Catherine Byles to Mather Brown, November 17, 1817, quoted in Swan 1936, 67. 33. See, for instance, Horace Binney's recollections of sitting for Stuart in 1800 in Miles 1995, 219–21. Sarah Wentworth Morton's daughter accompanied her mother on a visit to Stuart's studio in 1825 and described the artist "as eccentric, as dirty, & as entertaining as ever." Sarah Apthorp Cunningham, Dorchester, Mass., to Griselda Eastwicke Cunningham, Saulsbrook, Nova Scotia, April 11, 1825, Morton, Cunningham, Clinch Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston. 34. Sawitzky 1933b, 81. For Stuart's use of panels, see also Stuart 1877a, 381. Stuart's Horace Binney appears to be the first portrait Stuart painted on panel. Miles 1995, 221. 35. Oliver Wolcott, Jr., to John Trumbull, May 17, 1800, quoted in Miles 1997, 120–21. 36. Washington Allston, quoted in Morgan 1939, 3. 37. For Stuart's children and nephew, see Morgan 1939, 42–51; Powel 1920; and Mary Tyler Peabody Mann, Brookline, to Miss Rawlins Pickman, Salem, January 27, 1825, Horace Mann Papers II, reel 37. 38. Swan 1938, 308. 39. Sully's "Journal," July 28, 1807, 7; Sully 1869, 70; and Dunlap 1918, II, 250–51. 40. Jouett's notes were published in Morgan 1939, 80–93. 41. Staiti 1981, 271. 42. See Morgan 1939, 52–54, 59–63, 67–69. 43. For Stuart's burial as recorded in the records of Trinity Church, see Oliver and Peabody 1982, 829. Inventory of Gilbert Stuart's estate, Suffolk County no. 28699. For more on Stuart's death and an interpretation of his inventory, see Morgan 1934. Three editions of the 1828 exhibition catalogue were printed; see Yarnall and Gerdts 1986, I, 12. For more information on the exhibition see Swan 1940, 65–73, and Perkins and Gavin 1980, 133–36. Stuart's widow moved to Newport, where her death was noted in the Newport Mercury on October 11, 1845. |