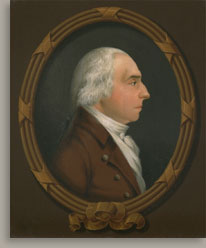

John Ritto Penniman John Ritto PennimanEdward Tuckerman, 1823 Description The sitter wears a reddish-brown coat over a white neck cloth. Three silver buttons are visible on the right side of the coat; each one is highlighted on either side with tiny curving strokes of brown and gray. Dark shadows to the lower left of each button, as well as prominent shadows cast by the folded-down collar and lapel, suggest that the light source is in the upper right. A bit of white-paint overlap on the collar and lapel probably was included to suggest hair powder. A trompe l’oeil oval frame surrounds the profile. The artist used tan paint to suggest three layers of gilded wood, joined together in seven places with crisscrossing straps and finished with a carved-ribbon ornament at the bottom of the oval. He used darker and lighter shades of tan to suggest the highlights and shadows. The background outside the trompe l’oeil frame was painted dark brown; inside the frame, the background is gray and appears to be slightly lighter in the upper portion of the oval. Along the inside of the frame, in the upper-left part of the oval, is a dark area intended to represent a shadow cast by the frame. A similar "shadow" appears in the brown background outside the frame, along the right and underneath the carved-ribbon ornament. Penniman signed his name in this shadow, along the lower-right side of the painted oval frame, just above the carved ribbon. Biography The couple had three daughters, followed by eight sons. The daughters, Elizabeth, Lucretia, and Susannah, were baptized at Trinity Church. The baptisms of five of their sons were recorded at Hollis Street Church in Boston, where Mrs. Tuckerman was admitted as a member on October 24, 1773.7 Susannah, the youngest daughter, died in childhood. Lucretia died in 1797, seven years after marrying Robert Wier (1768–1804).8 The eldest, Elizabeth (1768–1851), married Stephen Salisbury (1746–1829), a wealthy Worcester hardware merchant, in 1797; they were the grandparents of Stephen Salisbury III (1835–1905), who founded the Worcester Art Museum. Four of Edward and Elizabeth’s sons became Boston merchants: the eldest, Edward III (1775–1843), who had apprenticed with Stephen Salisbury; William (d. about 1855); Gustavus (1785–1860);9 and Henry Harris (1783–1860). Joseph Tuckerman (1778–1840) attended Phillips Academy and graduated from Harvard College in 1798. He became a Unitarian minister in Chelsea and was well known for his ministry to the poor in Boston.10 George Washington Tuckerman (about 1776–1837) eventually settled in Argentina, where he operated a cattle ranch.11 Little is known about Stephen (1782–1833), who died in Norridgewock, Maine, or about Charles (1787–1820), who died in Sturbridge, Massachusetts. Edward Tuckerman joined the Boston Artillery Company in 1765. He was a member of the Sons of Liberty and, from 1774 to 1776, remained active in the local militia. Later in the Revolution, he was a disbursing officer, supplying the Continental Army with funds allotted by the Massachusetts General Court for recruiting Massachusetts troops. He also provided flour to the Massachusetts soldiers.12 Tuckerman ran a bakery on Orange Street in Boston. After he successfully created a kind of biscuit that could stay fresh on long ocean voyages, his business expanded to include a factory—employing three hundred men—that supplied the durable bread to New England’s ports.13 Tuckerman also was a prominent public figure in Boston. He held several offices and served on numerous committees aimed at improving the common good. In 1782 he was elected the city’s surveyor of wheat, a position he held until his death, thirty-six years later.14 In May 1805, he was elected to a one-year term in the Massachusetts Senate, representing Boston; he was twice reelected.15 Ten years earlier, when the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association was founded to regulate apprenticeships and working hours in various trades (such as baking, shipbuilding, blacksmithing, and silversmithing), Tuckerman was chosen its vice-president, under Paul Revere; he served until 1798.16 In 1785 he served on a committee formed to consider building more schools in Boston. He also was a member of the committee that in 1792 catalyzed the repeal of a four-decade old colonial law forbidding "stage plays, and other theatrical entertainments" and that, two years later, established the Federal Street Theatre.17 In addition, he joined a group that in 1798 organized the Massachusetts Mutual Company, which sold fire insurance to Bostonians. Tuckerman was a charter subscriber to the Massachusetts General Hospital Fund and a member of the Massachusetts Society for the Aid of Immigrants. Tuckerman died on July 22, 1818, memorialized as "one of [Boston’s] most worthy, useful, and respectable citizens." 18 His estate was valued at more than $51,000. He was laid to rest in the city’s Central Burial Ground alongside his wife, who had died thirteen years earlier. In 1836 their remains were reinterred in a Mount Auburn Cemetery lot that their son Henry owned.19 Analysis

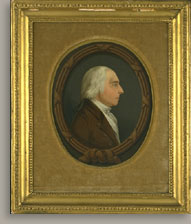

The details of the 1823 commission that resulted in this posthumous portrait can be traced in family letters. Early that year, Stephen Salisbury II wrote to his mother, Elizabeth, suggesting that she join other members of the family who were having Chester Harding paint their portraits. She replied that she did not think the time was right. But, she added, "I wish my brother Joseph would employ [Harding] to copy that of my Father which he possesses, and which he said he would have done for me, unless he has already engaged some one to do it."20 Because she evidently did not know whether Joseph had secured an artist for that task, Stephen promised her that he would remind his uncle to do so.21 Unbeknownst to Elizabeth, her brother Henry Harris Tuckerman had already commissioned John Ritto Penniman to copy the pastel portrait of their father to which she referred in her letter, an image that had been produced nearly two decades earlier. Penniman’s inscription on the back of the Worcester oil painting provides important details about the original work: he wrote that he copied it from a "Profile Painted in Crayons/ by G. Schipper in 1804." 22 Although neither Edward Tuckerman nor his children identified the artist of the pastel portrait in their correspondence or records, Schipper was indeed active in Boston in the early 1800s and, for reasons discussed below, was probably the one who produced the image. A Dutch pastel and miniature painter who arrived in the United States in 1802 after training in Europe, Schipper plied his trade briefly in New York and Charleston, then settled in Boston. At the time, only a few artists there were working in pastels. From the fall of 1803 until sometime after the following January, he worked in a drawing room in the house of a Mr. Wakefield, on Milk Street.21 In January 1804, he ran an advertisement in three issues of the Columbian Centinel and Massachusetts Federalist:

Schipper guaranteed his likenesses, and they were inexpensive: the seven-dollar price included the frame. Before Schipper left Boston, in the summer of 1804, Edward Tuckerman was one of his patrons. In June, Schipper was advertising his services in the Salem newspapers, and then in August in the Worcester newspapers, at a higher price—ten dollars per portrait.23 The Tuckermans had begun looking for an artist to copy the pastel of their father in 1822, but the effort got off to a bad start. As Henry wrote to Elizabeth, "[A]t the time brother Joseph brought the picture to town . . . we made enquiry for a crayon painter but could find none, and the glass having been broken the Picture & frame was left with me to get repair’d."24 In November or December, Henry took the pastel in its broken frame for repair to John Doggett (1780–1857), a carver and gilder who made cabinets, looking-glasses, and frames and also sold pictures; his establishment was located just down Market Street from Henry’s own textiles shop.25 When Henry asked if he could recommend an artist to copy the pastel, Doggett suggested Penniman. He told Henry, however, that Penniman did not work in pastels and warned that he would have to "take the hazard of his success." After interviewing the painter several times, Henry hired him to copy the pastel in oils for fifteen dollars. He also ordered a three dollar frame from Doggett.26 It is not surprising that Doggett recommended Penniman. The two had known each other since their early days in Roxbury, where their shops were nearby those of other artisans, including the clockmakers Simon and Aaron Willard, for whom Penniman had worked. In 1803 Penniman painted looking-glass tablets and a shop sign for Doggett and also bought gold leaf and picture frames from him.27 And by 1822, Penniman’s studio was at 73 Market Street, making him a business neighbor of both John Doggett and Henry Harris Tuckerman.28 Penniman’s trade card from about 1822 (Joseph Downs Manuscript Collection, Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, Winterthur, Delaware) does not list the copying of portraits among his skills. However, after completing the Tuckerman commission, he is known to have copied at least one other likeness, James Frothingham’s (1786–1864) portrait of Governor John Brooks (1825, Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts). Later, Henry explained that he had kept the hiring of Penniman a secret from his siblings, including Joseph, until he could see the work and decide if it was successful. He had to wait three months.29 Penniman completed the copy on February 5, 1823, and, Henry wrote his nephew Stephen Salisbury II the next day, "has already ‘given two sittings to two other Copys’ but I am under no obligation to take them."30 Gustavus Tuckerman "at once order’d one for himself," and William Tuckerman requested the other.31 On February 17, Henry informed Elizabeth that if she wanted the artist to start a fourth copy, she should reply quickly. Appending a message to the same letter, Joseph praised the sole completed copy: "[It] is as perfect as, I think, could be taken. It has more life in the flesh, than the original; & to a very considerable degree has avoided an unpleasant expression, which I always regretted in my picture." He encouraged Elizabeth to order one.32 She did so quickly, sending the request via her son. On February 20, Henry wrote Stephen that he would "immediately" ask Penniman to begin a copy for her. "I hope & trust she will find no occasion to regret the possession of the Picture," he added. "[H]er instructions I promise faithfully to report, and feel persuaded that Mr P will in this fourth trial furnish evidence of improvement & give entire Satisfaction."33 Henry sent Elizabeth her copy—the work that is now in the Worcester Art Museum’s collection—on March 27. In an accompanying note, he wrote that Penniman had asked him "to say that he thinks he has improv’d in this regard that of any of the others in retaining the countenance as familiar to him & various other persons at the South End who have seen it. I hope it will prove acceptable."34 It did not. She wrote Henry that she found her father’s expression unduly stern and hoped Penniman could make some changes, beginning with the size of her father’s face, the darkness of his complexion, and the incorrect color of his eyes. As if to soften her tone, she added in a postscript, "[N]otwithstanding the faults I have pointed out, the likeness is strong—it would be known by anyone." Yet, she reiterated, "if the complexion could be made fairer & the eye, & eyebrows lighter, the Picture would be much improv’d."35 If Henry replied to his sister’s letter, there is no record of it. And, despite the objections she raised, Worcester's Edward Tuckerman displays no evidence that Penniman altered it according to Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury’s wishes. For instance, the eyes are gray and not blue, and the brows are dark—as she described them.

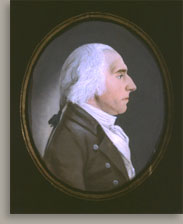

It is unclear what Jane meant by "the circumstances under which it was taken." She might have been referring to the possibility that Penniman used either a physiognotrace, a camera obscura (as Schipper had in making his likenesses), or a similar mechanical device to trace the original work. In the letter he wrote Stephen a day after receiving the initial copy, Henry alluded to the use of such tools, noting that "the mode of taking the outlines of the face admit of no possible variation." He added that this "mode" ensured that "the profile is exact, as taken from life."38 Although subtle distinctions exist between the oil copy Penniman made for Jane and Gustavus (fig. 2) and the one he did for Elizabeth (the Worcester Art Museum’s painting), there is additional evidence to support the idea that he used a mechanical device to replicate the original pastel. The dimensions of Jane and Gustavus’s copy are practically identical to those of Elizabeth’s. For instance, in both images the measurement across the subject’s head is the same (just over three and one-eighth inches), as are the length and width of the trompe l’oeil frame. Moreover, a comparison of the original pastel (fig. 1) with the two oils reveals the same prominent brow and curve of the nose in all three images. However, the shadow around the painted frame is narrower in Jane and Gustavus’s copy than in Elizabeth’s. Also, the signature in the former version, even though it is in the same place as in Elizabeth’s—at bottom right, along the outside edge of the painted frame—reads J. R. PENNIMAN, PAINTER." As well, there are variations in the carved-ribbon ornament at the base of each painted trompe l’oeil frame, in the hair, and in the queue ribbon. Penniman’s use of cross-hatching to render the shadows of the coat in Elizabeth’s copy is an added flourish, not present in Jane and Gustavus’s copy. This feature, and the other slight differences between the two works, suggest that the artist was still trying to improve and experiment in the final version, which he made for Elizabeth.39

Despite Penniman’s identification of Schipper as the artist of the original pastel on the back of Edward Tuckerman, there has been some confusion about this attribution, stemming from an erroneous assertion by the family genealogist, Bayard Tuckerman (b. 1855). Bayard, a great-grandson of the subject, wrote in his Notes on the Tuckerman Family (1914) that James Sharples (1751/52–1811) did pastel portraits of Edward Tuckerman and his eight sons.42 Although in his book Bayard reproduced the pastel of Edward that Joseph owned (which, as we know from the above-cited family correspondence, was the pastel that Penniman copied and noted in his inscription was by Schipper), he identified the artist as Sharples and made no mention of Schipper. Bayard also seems not to have known about the Penniman commission, because he did not mention the four oil copies Penniman had made. Instead, he wrote that Robert W. Weir (1803–1889) painted several posthumous oil copies of the pastel portrait, adding that Harper Pennington (1855–1920) produced two enlarged copies for himself and his brother Paul.43 Regrettably, there has not been a great deal of scholarship on early American pastelists. As a result, many pastels have over the years been incorrectly assigned to a few known artists, including members of the Sharples family.44 That explains why Bayard Tuckerman’s attribution of the pastel to James Sharples was subsequently repeated by various scholars. Katherine McCook Knox published the work in her 1930 book on Sharples. The same year, Harriette Forbes reproduced Penniman’s Edward Tuckerman and wrote, mistakenly, that it probably was a copy of a Sharples pastel; she was unaware of Penniman’s inscription on the back of his canvas. The pastel also was attributed to Sharples when exhibited at Washington’s Corcoran Gallery of Art in 1952. More recently, Penniman authority Carol Damon Andrews added to the confusion by writing that Penniman’s portrait was after Schipper and that the Schipper was, in turn, after Sharples. Bayard Tuckerman’s illustration of the Schipper pastel, incorrectly identified as a Sharples, indicates that Penniman’s portrait was preceded by only one work by one artist—not two, as Andrews asserted without basis.45

Notes 1. Tuckerman 1914, 19. 2. Ibid., 22, 24; Holman 1945, 11, 31. 3. Harris identified himself as a baker in his will. See Will of Stephen Harris, 1773, Suffolk County no. 15425. For his obituary, see Boston Gazette and Country Journal, May 17, 1773. 4. Oliver and Peabody 1982, 729. Elizabeth Harris was Edward Tuckerman’s first cousin once removed of the half blood. 5. Edward was baptized on February 19, 1775; William was baptized on June 10, 1780; Stephen was baptized on March 24, 1782; Henry Harris was baptized on September 28, 1783; and Charles was baptized on April 29, 1787. See Hollis Street Church Records, New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston (hereafter cited as NEHGS), mss 293a, folder 6, p. 418. No baptisms were recorded for George Washington, Joseph, or Gustavus Tuckerman. For those three, see Tuckerman 1914, 61, 64, 66. The Hollis Street Church has no record of Edward Tuckerman’s membership. However, the family genealogy notes that he joined that church; also, "a Pew in Mr Hollis’s meeting house" is listed in his estate inventory. See Tuckerman 1914, 45, and inventory of Edward Tuckerman, 1818, Suffolk County no. 25618. 6. Tuckerman 1914, 48; Oliver and Peabody 1982, 556, 560, 562. Lucretia Tuckerman and Robert Wier’s marriage is recorded in Hollis Street Church Records, NEHGS, mss 293a, folder 6, p. 418. For Lucretia’s death, see Columbian Centinel (Boston), October 11, 1797. 7. For Edward Tuckerman III, see Tuckerman 1914, 52–61. William and Gustavus Tuckerman were business partners. For an advertisement of their "Hard Ware Goods," see Columbian Centinel (Boston), November 3, 1819. Henry Harris Tuckerman advertised a wide variety of fabrics in the same newspaper, December 1, 1813, and September 11, 1822. 8. See Roberts II, 1897, 324–25; Elliot II, 1910, 103–17; Wright 1992; and Wach 1993. The Joseph Tuckerman Papers are in the Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston. 9. Tuckerman 1914, 64–65; Columbian Centinel (Boston), January 31, 1838. 10. Roberts II, 1897, 136–37; Mackenzie 1914, 538; Tuckerman 1914, 27, 33; Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors XVI, 1907, 126. 11. Tuckerman 1914, 27–28. The Boston directories for 1798, 1800, 1803, and 1805–7 list Edward Tuckerman as a baker with a shop on Orange Street. Boston Directory 1798, 114; 1800, 108; 1803, 124; 1805, 125; 1806, 124; 1807, 147. References to Tuckerman’s business can be found in the Caleb Davis Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston. 12. Mackenzie 1914, 538. See also Boston Town Records 1903, 56, 223, 248, 279, 322, 387, 423. 13. Tuckerman 1914, 32–33; Massachusetts Legislative Biography card file, State Library of Massachusetts, Boston. 14. Tuckerman 1914, 28; Buckingham 1853, 10, 22, 23. 15. Boston Town Records 1903, 74, 314. 16. Columbian Centinel (Boston), July 22, 1818. 17. Tuckerman 1914, 47; records of Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Massachusetts, lot 496. For the will and inventory of Edward Tuckerman, Suffolk County no. 25618. 18. Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, Worcester, to Stephen Salisbury II, Boston, January 14, 1823, Salisbury Family Papers, American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts (hereafter cited as SFP, AAS), box 21, folder 1. 19. Stephen Salisbury II, Boston, to Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury and Stephen Salisbury I, Worcester, January 15, 1823, SFP, AAS, box 21, folder 1. 20. In a letter to his nephew, Henry also confirmed that the portrait Joseph owned was Penniman’s source and that it was a pastel: "Penniman has compleated one Copy of our dear Father from the Crayon—belonging to Joseph." Henry Harris Tuckerman, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury II, Worcester, February 6, 1823, SFP, AAS, box 21, folder 1. 21. For Schipper, see Riger 1990 and Hyer 1952. 22. Columbian Centinel and Massachusetts Federalist (Boston), January 14, 21, 28. The same advertisement ran in all three issues. 23. Salem Gazette, June 5, 8, 12, 15, and 19, 1804; and Massachusetts Spy or Worcester Gazette, August 1, 1804. In Worcester that year he drew two likenesses of the Massachusetts Spy editor Isaiah Thomas (1749–1831) and one each of his wife, son, and daughter-in-law (American Antiquarian Society, Worcester). 24. Henry Harris Tuckerman, Boston, to Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, Worcester, February 12, 1823, SFP, AAS, box 21, folder 1. 25. My surmise as to when Henry brought pastel to Doggett is based on his February 12, 1823, letter to his sister. In discussing the copy he had commissioned from Penniman, he wrote, "For the past three months I have been waiting upon this man [Penniman]." Henry Harris Tuckerman to Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, February 12, 1823. An advertisement Doggett placed in the Columbian Centinel (Boston) from September 7, 1822, to January 15, 1823, announced that his firm had moved "from 28 to No. 14 Market-Street." His picture gallery was at No. 16 Market Street. See the advertisement for work displayed there in Columbian Centinel, August 21–October 12, 1822. Henry Harris Tuckerman placed an ad in the September 11, 1822, issue of the same newspaper announcing, "New Goods. H. H. Tuckerman, Nos. 1 & 3, Market-Street." 26. Henry Harris Tuckerman, Boston, to Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, Worcester, February 12, 1823, SFP, AAS, box 21, folder 1. 27. In a daybook he kept from January 7, 1803, to February 4, 1807, John Doggett recorded his transactions with the artisans of the Meeting House Hill Section of Roxbury, including Penniman. See John Doggett accounts, Joseph Downs Manuscript Collection, Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, Winterthur, Delaware. See also Andrews 1981, 150, and Swan 1929. A label for John Doggett, "Gilder, Looking Glass & Picture Frame Manufacturer, Roxbury," designed by Penniman in 1810, provides more evidence of the continuous relationship between the two artisans. See the reproduction of the label in Comstock 1964, 684. 28. The Boston city directory for 1822 lists John R. Penniman as a painter residing at 1 Warren and 73 Market Street, as cited in Andrews 1981, 161 n. 19. 29. Henry Harris Tuckerman to Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, February 12, 1823. 30. Henry Harris Tuckerman to Stephen Salisbury II, February 6, 1823. 31. Joseph Tuckerman and Henry Harris Tuckerman, Boston, to Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, Worcester, February 17, 1823, SFP, AAS, box 21, folder 1; Henry Harris Tuckerman to Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, February 12, 1823. 32. Joseph continued, "[N]othing deters me from having a copy, than the circumstance, that I do not feel able to afford it." Joseph and Henry Harris Tuckerman to Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, February 17, 1823. 33. Henry Harris Tuckerman, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury II, Worcester, February 20, 1823, SFP, AAS, box 21, folder 1. 34. Henry H. Tuckerman, Boston, to Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, Worcester, March 27, 1823, SFP, AAS, box 21, folder 1. Both Penniman and Edward Tuckerman had attended the Hollis Street Church and lived on Orange Street. See Hollis Street Church Records, NEHGS, mss 293a, folder 5, p. 327, and folder 6, p. 418. 35. Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, Worcester, to Henry Harris Tuckerman, Boston, March 31, 1823, SFP, AAS, box 21, folder 1. 36. For a record of this portrait, see Lydia Dufour, Reference Letters, Frick Art Reference Library, New York, to Laura K. Mills, June 19, 1998, and Morgan 1969, 34. Gustavus’s copy descended, in turn, to his son Gustavus (b. 1824), to his daughter Jane (dates unknown), to her brother Eliot (1872–1959), and then to Eliot’s daughter Emily Tuckerman Allen (Mrs. Henry Freeman Allen), the present owner. 37. Jane Francis Tuckerman, Boston, to Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, Worcester, April 10, 1823, SFP, AAS, box 21, folder 1. 38. Henry Harris Tuckerman to Stephen Salisbury II, February 6, 1823. 39. The mahogany panel of Jane and Gustavus’s copy appears to have been cut down to an oval shape only slightly larger than the trompe l’oeil frame that is part of the image. Examination of the back of the panel faintly reveals part of Penniman’s inscription, which has been hidden by a small marine scene painted on top of it. 40. Unfortunately, I have only seen this work in a color transparency. The image and frame measurements were supplied by the owner, who also noted that the frame appeared to be similar to that on the Worcester Art Museum’s version. Mrs. George F. B. Johnson, Jr., to Laura K. Mills, April 28, 2000. 41. Mentioning George in a letter to his sister Elizabeth, William reported, "I have just heard verbally how much he was pleased with the picture of father, we so long ago sent him." William Tuckerman, Boston, to Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, Worcester, August 4, 1829, SFP, AAS, box 23, folder 1. 42. Tuckerman 1914, 43–45, 113. Edward Tuckerman’s estate inventory lists engravings, an oil portrait of George Washington, and "9 pictures 75c." Inventory of Edward Tuckerman, Suffolk County, no. 25618. The coincidence of a group of nine pictures in the inventory does not support the Sharples attribution, but it lends some credence to Bayard’s claim that Tuckerman’s eight sons also sat for pastels along with their father. According to him, the pastel of Edward Tuckerman, Jr., was handed down to a grandson, Dr. Frederick A. Tuckerman of Amherst; and the pastel of Joseph Tuckerman was owned by the heirs of Joseph’s daughter Mrs. John Phillips Spooner. Unfortunately, the present whereabouts of those two works are unknown. In 1959 pastel profile likenesses of William Tuckerman and George Washington Tuckerman entered the collection of the Glass-Glen Burnie Museum, Winchester, Virginia–attributed to James Sharples. It is more likely, however, that they are the work of Gerrit Schipper. Both portraits feature the feigned oval and lighter area behind the sitter that are hallmarks of Shipper’s images. The two pastels had been owned by Arthur J. Sussel (d. 1958), a Philadelphia collector. See Sotheby Parke-Bernet Galleries 1959, lot 618; and David Meschutt to Laura K. Mills, September 27, 1999. Further study of these pastels is necessary to determine whether they are related to the pastel portrait of Edward Tuckerman (fig. 1). 43. Bayard Tuckerman noted that the original pastel "descended through my grandfather and uncle Joseph to my brother Walter Cary." Tuckerman 1914, opp. 24, 44–46. Bayard was the grandson of Joseph Tuckerman and the son of Lucius Tuckerman (1818–1890). The uncle he mentions was his father’s brother, Joseph Tuckerman II (d. 1898). In 1876 Walter Cary Tuckerman (1849–1894), an amateur sculptor, did at least two plaster bas relief copies (private collection and Worcester Art Museum) after the pastel of Edward Tuckerman while that work was in his possession. After he died, the pastel went to his son Walter Rupert Tuckerman (1881–1961). Knox 1930, 97; Corcoran 1952, 28, cat. no. 107. The work then descended to Edith Tuckerman Biays, Walter Rupert’s daughter. Edith’s daughter, Mrs. Richard W. Germann, currently owns it. Although neither the Weir nor the Pennington copies has been located, a granddaughter of Bayard Tuckerman owns two profile portraits of Edward Tuckerman; in them, the subject has blue eyes, and he wears a blue coat rather than a brown one. 44. Doris Devine Fanelli, Chief, Division of Cultural Resources Management, Independence National Historical Park, Philadelphia, to Laura Mills, [spring 1998], and Milley 1975. 45. Andrews 1981, 158. |

_EdTuck.jpg)