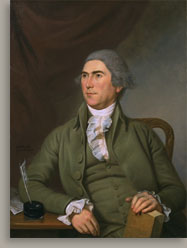

Charles Willson Peale Charles Willson PealeCharles Pettit, 1792 Description Pettit’s pose is relaxed, and his proper right elbow and forearm rest on a table at the left side of the composition. His right hand extends over the front edge of the table. His left hand rests atop a brown, leather-bound book; a pentimento on the lower half of the book suggests that Peale added this object to the painting after the composition was nearly complete. Pettit sits in a carved, Chippendale-style side chair, the top corner of which is visible behind his left shoulder. The table runs parallel to the bottom edge of the painting. A black inkwell holds a quill; the inkwell is reflected in the polished wooden tabletop. Under Pettit’s elbow are several documents, illegibly inscribed. The sitter wears a green suit, probably of wool, that has a high collar and large, cloth-covered buttons. The matching waistcoat has small, cloth-covered buttons; the second and third from the top are undone. He also wears a white stock and shirt ruffle and a single ruffle at each cuff. Peale suggested the horizontal folds in Pettit’s waistcoat by varying the green tones and by reinforcing the depths of the folds with dark-brown paint. A swag of dark-red drapery behind the figure hangs from the upper left corner to the upper right part of the top edge of the composition. The background varies from dark gray on Pettit’s left to light gray along the right side of the image. A strong light, coming from the upper left to the lower right, illuminates Pettit’s face and casts shadows on the proper left side of his body. Shadows also help create the illusion of three-dimensionality in both Pettit’s form and clothes. Biography Throughout his career, Pettit was active in public life as well as in commerce and the law. He attended the Presbyterian Church on Arch Street in Philadelphia, where he was appointed one of the managers of a lottery to raise funds for the construction of a steeple on the unfinished edifice.8 He also was one of the managers of a lottery organized to support the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University).9 And in 1765, he was among the founding donors to the Pennsylvania Hospital, the first institution in America where the poor could receive medical attention.10 Pettit’s brother-in-law Joseph Reed was appointed provincial surrogate of New Jersey in 1767 by William Franklin, the last of the royal governors.11 Pettit himself was subsequently appointed surrogate under Franklin and, in 1769, became deputy secretary of the province.12 Pettit moved from Burlington to South Amboy with Franklin, but their relationship was severed when the governor decided to maintain his support of British authority and Pettit sided with the Whigs.13 He was Franklin’s secretary from 1772 to 1774 and worked for Governor William Livingston in the same capacity from 1774 to 1778.14 Pettit also served in colonial New Jersey as clerk of the council, of the supreme court, and of the pleas court.15 In 1778, as Pettit began focusing intently on the war effort, he accepted a position as assistant quartermaster-general of the Continental Army, which he maintained until 1781.16 When General Nathanael Greene (whom Pettit had known since childhood) resigned as quartermaster-general, Pettit was offered that position but declined the promotion.17 In a 1780 letter to Greene, Pettit poignantly captures the tribulations of the war:

Despite Pettit’s discouragement, he remained active in the war effort. Pettit continued his public career after the Revolution in state and federal government. He served one term apiece in the Pennsylvania state legislature (1783–84) and the U.S. House of Representatives (1785–87).19 In 1788 he promoted the ratification of the Constitution at the general convention that met in Harrisburg to decide this matter.20 Politically—like Charles Willson Peale—he initially was a Pennsylvania Constitutionalist and then a Democratic-Republican.21 In addition to his public career, Pettit resumed his role as a successful Philadelphia merchant after the war. He is listed in the city’s 1785 directory as a merchant in partnership with his son Andrew (1762–1837) at "317, River-side" and "203, Water-street," an address that was perhaps a combination office-warehouse.22 By 1791 the Pettits’ firm had moved to 9 South Water Street, and by 1793 had taken on Andrew Bayard as a partner.23 Bayard was Charles Pettit’s son-in-law, having married his daughter Sarah in 1792. Pettit was apparently retired from active involvement in the business by 1804, when he appears in the directory as a gentleman.24 Pettit also was an officer of the Insurance Company of North America, which was established in 1792 to offer financial protection against marine shipping losses as well as against the risks of fire and death. He was among the fifteen original directors of the company and served twice as its president.25 Pettit was involved in his city’s intellectual life as well. In 1785 he served on the board of visitors of the Young Ladies Academy of Philadelphia, an institution founded on the republican principal that women should receive the kind of general education that was traditionally reserved for men.26 He was a trustee of the University of Pennsylvania from 1791 to 1802.27 Finally, he was a member and officer of the American Philosophical Society, to which Peale also belonged.28 He died in Philadelphia on September 4, 1806. Analysis In Charles Pettit, Peale moved beyond the traditional representation of a merchant or public official who appears to pause amid his work to return the gaze of the artist or viewer. Portraits of that type were common throughout the eighteenth century, as in Joseph Badger’s Cornelius Waldo and Joseph Blackburn’s Colonel Theodore Atkinson. Peale also employed that convention early in his career, in such works as Samuel Chase (about 1773, Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore), John Bayard (1780, Philadelphia Museum of Art), Benjamin Rush (1783, Winterthur Museum, Winterthur, Delaware), and Governor Thomas McKean and His Son, Thomas, Jr. (1787, Philadelphia Museum of Art).30 But in the present work, he seems to allude more broadly to Pettit’s contributions to the new Republic. Pettit had played an important role in the Revolution as assistant quartermaster-general under Nathanael Greene, served in the Pennsylvania and United States legislatures, and advocated Pennsylvania’s ratification of the U.S. Constitution. Rather than specify any one of those events, however, Peale chose to give his sitter a distant gaze that suggests he is a public-spirited man who acts dispassionately for the common good.

Charles Pettit was painted in 1792. According to family tradition the painting was commissioned as a gift to the sitter’s son Andrew to celebrate his marriage on December 8, 1791, to Elizabeth McKean, the daughter of Thomas McKean.32 McKean family lore similarly contends that Peale’s Thomas McKean (1791, National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.) was commissioned as a gift to his daughter marking the same occasion.33 Although the two portraits were painted in different sizes—Pettit’s is a kit-cat, whereas McKean’s is a bust-length—they do share at least three elements: McKean’s head is turned three-quarters left, he wears a green suit, and there is a red drapery in the background.34

2. Ibid. 3. For Pettit’s marriage to Sarah Reed, see ibid. For his residence in Trenton, New Jersey, see Pennsylvania Gazette, February 9, 1758. 4. Sellers 1952, 170; Doerflinger 1986, 254. 5. Pennsylvania Gazette, January 29 and February 12, 1761; March 15 and July 19, 1764; February 28, May 9, and July 4, 1765. 6. Pennsylvania Gazette, December 23, 1762. 7. Appletons IV, 1900, 747. 8. Pennsylvania Gazette March 12, 1761. 9. Pennsylvania Gazette July 16, 1761. 10. Pennsylvania Gazette July 11, 1765. 11. Appletons IV, 1900, 747. 12. Ibid. 13. Ibid. 14. Thorpe 1925, 24. 15. Congress 1971, 1536. 16. Appletons IV, 1900, 747; Congress 1971, 1536. 17. Appletons IV, 1900, 747; James 1942, 57. 18. Pettit to Greene, February 26, 1780, as quoted in Doerflinger 1986, 232. 19. Appletons IV, 1900, 747. 20. Ibid. 21. Sellers 1952, 170. 22. Macpherson 1785, 105. 23. Biddle 1791, 101; Hardie 1793, 112; Hardie 1794, 9, 120. 24. Robinson 1804, 181. 25. James 1942, opp. 64. 26. "Intelligence," Columbian Magazine 1: 9 (May 1787): 447. 27. Appletons IV, 1900, 747. 28. Ibid. 29. Richardson 1983, 68–75; Fortune and Warner 1999, 150, 152. 30. Sellers 1952, 187, 294, 296, 312. 31. Fortune and Warner 1999, 126, 130–32. Interestingly, in Peale’s first portrait of George Washington (1772, Washington and Lee University, Lexington, Virginia), the subject stands, but his head is turned three-quarters left in a distant gaze. 32. Buchanan 1890, 120, 127; "Portrait from Life of Col. Charles Pettit," August 29, 1917, ms., object file, Worcester Art Museum. 33. Buchanan 1890, 120. Sellers doubts the veracity of the McKean tradition (1952, 137). 34. Sellers 1952, 137. 35. Park 1926, II, 593. |