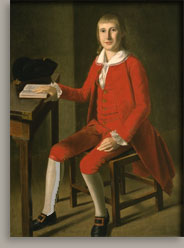

Ralph Earl Ralph Earl

William Carpenter, 1779

Description

William Carpenter is a full-length portrait of a boy seated at a desk. He is turned three-quarters left, and his gaze is directed at the viewer. Carpenter’s blond hair is cut in bangs across his forehead and hangs in loose curls at his shoulders. His eyes are blue. He wears a solid red waistcoat, coat, and pants that extend just below his knee. Each of these garments is trimmed with gold-colored buttons decorated with a circle at the center and a radial, flowerlike or sunburstlike pattern. The pant cuffs are trimmed with an open oval buckle. A white lace-edged ruffle and collar are visible at the boy’s neck, and he wears white ruffled cuffs and white stockings. His black leather shoes are decorated with large, gold-hued rectangular buckles. William Carpenter’s haircut and clothing are typical of an English boy of his time, fashionable yet slightly provincial in their color and uniformity.1 His right foot rests squarely on the floor, and his left heel is slightly raised, helping to convey the sense that he has just shifted to look at the viewer. Carpenter sits on a linear, joined stool with a black leather seat, and his coat drapes over the back edge; this seat is placed on a three-quarter angle matching the boy’s pose. His left hand rests on his thigh, and his right hand holds open an unidentifiable book on a narrow folding table. The leaf of the table is folded shut, and a brass hinge is exposed at the right-front corner. Earl’s drawing is inaccurate in that the front corner of the table ought to be higher or the back corner lower to define a flat, rectangular surface. Resting on the table is the boy’s black hat, cocked on three sides and decorated with gold braid at the back and a gold tassel at the opposite corner. Both the book and the hat are faintly reflected in the surface of the tabletop.

The portrait is set in an interior that is simply defined by olive tones on the wall and browns on the floor. A single light source flows from the left side of the painting, casting shadows on the right side of the boy’s face and body and on the floor to the right and behind him. This light, which seems to define a wall, leads the eye forward to the boy at left. A shadow appears to indicate an adjoining, receding wall to his right. Alternatively, the left side could define a box of light coming from a window or door. However, the floor lines, which run nearly parallel but not continuously, do not support either interpretation of the space. The edge of the floor to the left of the figure is higher than the one to his right. One suspects that Earl intended to define a projecting corner behind the boy’s forearm but that he failed to adjust the floor line to recede toward the left side of the painting.

Biography

Baptized on November 5, 1767, William was about twelve years old when he sat for this portrait. He and his sister Mary Ann were the namesakes of their parents, William and Mary Carpenter. The Carpenter family resided near Norwich in Aldeby, Norfolk County, in eastern England. The social position of the children’s father was noted as "yeoman" at the time of the children’s baptisms and "Gent[leman]." on his grave marker.2 The younger William Carpenter and his wife, Louisa, raised eight children at Toft Monks, also in Norfolk County, near Norwich. The sitter was recognized as "Esq[uire]." on his marble burial tablet.3

Analysis

Ralph Earl’s presence in East Anglia suggests the continuing support and guidance of Captain John Money (about 1752–1817), whose home, Trowse Hall, was two miles from Norwich. Earl was a Loyalist who fled to England during the Revolution, arriving in April 1778, the year before he painted the Carpenter children’s portraits. Earl was assisted in his escape by Money, who was quartermaster general to General John Burgoyne (1722–1792). The artist did not find an immediate source of income in England and filed a petition with the British government for financial relief. In it, he noted his "hopes to have supported himself until the present Contest with the Colonies had subsided but now finds it impossible to subsist longer in the manner he has thus far done, being reduced to the utmost Distress. [O]r would by no means have troubled your Lordships." John Money appended an endorsement to the petition, noting the artist’s loyalty to the Crown: "I found him a persecuted Man in the province of Connecticut & his life in Danger & at the Request of the Friends of Government assisted him making his Escape[.] I was frequently Assured that this Gentleman saved a party of the Kings Troops from being cut off from the East end of Long Island . . . [by his] sending them Timely information."4

Evidently, Earl’s petition failed, and Money took additional steps to secure income for the artist. The proximity of the Carpenter family to Money’s home suggests that it was he who introduced the American to some of his first English patrons. Twenty-four works are ascribed to Earl’s stay in England, including the likenesses of the Carpenter children and Portrait of a Man with a Gun (1784). Earl’s success there also included the exhibition of four paintings at the Royal Academy between 1783 and 1785, the year he returned to America.5

Earl’s earliest surviving signed and dated works and his first known commissions in England, William Carpenter and Mary Ann Carpenter (Mrs. Thompson Forster) were painted in 1779 in Aldeby, sixteen miles from Norwich. The two are companion portraits, each presenting a seated child reading. The images are composed quite similarly, with a desk at the left side and the child in each seated slightly off-center and facing three-quarters left. Earl’s depiction of William Carpenter is spare and simple compared to that of the boy’s sister. The subject sits on a joined stool instead of on an upholstered chair; the desk is unadorned rather than draped; and the floor is bare wood rather than carpeted as in the girl’s portrait. William’s clothes are likewise plain, in contrast to Mary Ann’s laced and garlanded dress. These various details seem intended to contrast the genders of the two sitters.

|

|

Figure 1. Ralph Earl, Roger Sherman, about 1775–76, oil on canvas, 64 5/8 x 49 5/8 in. (164.2 x 126 cm), Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut. Gift of Roger Sherman White, B.A., 1899, LL.B. 1902.

|

|

Earl’s handling of William’s portrait reflects continuity with the style seen in his earlier New Haven portraits, most closely resembling Roger Sherman (fig. 1). Both paintings feature full-length seated poses in which the subject is turned leftward and looks at the viewer. The poses are further alike in that the sitter’s hand rests on his left leg in each painting. Both subjects are illuminated by a light source that enters from the left and casts shadows of the figure and furniture on the floor. A linear design and strong use of light to create planar modeling also connect the two portraits stylistically. Still, there are important differences between the two compositions. The English portrait does not contain the drapery that hangs behind Roger Sherman. Instead, the interior is developed by the inclusion of the desk, book, and hat beside the figure. These elements add a narrative quality that is absent in Earl’s portrayal of the American patriot, which is more fully focused on Sherman’s likeness and personality. Also, Carpenter appears slightly less static than Sherman, an impact that is achieved by the less frontal view of the boy and the lifting of his left heel off the floor. The child’s striking red costume and white stockings also present a vivid contrast to Sherman’s brown clothes and black stockings. Perhaps the fact that William Carpenter has survived in better condition than Roger Sherman helps account for the view of several historians that the English portrait represents a significant improvement in Earl’s ability.6

Notes

1. Aileen Ribeiro, costume notes to catalogue entry in Kornhauser 1991a, 115.

2. Louisa Dresser, curator at the Worcester Art Museum from 1932 to 1972, visited Aldeby and Toft Monks in 1957 and transcribed the gravestones of several generations of Carpenters there, including William, Sr., William, Jr., and Mary, the mother of Earl’s portrait subject. Dresser also made notes from the parish baptismal records. Her notes are preserved in the Worcester Art Museum object file and cited in Sawitzky and Sawitzky 1960, 39 n. 17.

3. Ibid.

4. Ralph Earl to the Lords Commissioners of the Treasury, loyalist petition, with supporting letter from John Money, January 28, 1779, Public Record Office, London, ref. no. AO 13/4. I thank Maxine Tourigny for securing a copy of this important document for the museum’s files.

5. Kornhauser 1991a, 19, 21.

6. There is a long tradition of comparing Roger Sherman and William Carpenter, especially since few portraits are known from Earl’s hand prior to his time in England. Alan Burroughs saw continuity in the "plainness of vision" in each of these portraits (American Art Portfolios 1936, 34). William Sawitzky, by contrast, saw a dramatic advance in the artist’s style. He believed, furthermore, that the Carpenter portraits hinted that "Earl by that time may have had the benefit of either lessons, or, at least, constructive criticism, most likely from his countryman Benjamin West" (Sawitzky 1945, n.p.). Sawitzky later became even more confident about this hypothesis, arguing that West must have taught Earl because the style of the Carpenter portraits strongly suggests that he had seen a group of West’s of Eton-leaving portraits. In particular, West’s Harry Fetherstonhaugh (about 1772, Eton College) depicts a seated young man holding a book, and Charles Maynard (about 1771, Eton College) shows its subject with a pen in his right hand and papers on a tabletop under his left hand (Sawitzky and Sawitzky 1960, 20). For West’s Eton portraits, see Von Erffa and Staley 1986, nos. 617 and 656, pp. 506, 528.

Elizabeth Kornhauser saw a finer use of color and a greater sense of ease in the Carpenter portraits than in the Sherman but also evidence of Earl’s abiding interest in imitating Copley’s use of strong light and shadow. She was not convinced that Earl had studied with West prior to painting the two children (Kornhauser 1988, 52–53; and 1991a, 19). |

Ralph Earl

Ralph Earl