Ralph Earl Ralph Earl

Mary Ann Carpenter (Mrs. Thompson Forster), 1779

Description

This is a full-length portrait of a seated girl who is turned slightly to the left. Her arms, neck, and face are painted in light pinks, with darker pink on her cheeks, chin, and knuckles. Earl uses gray to define shadows in her flesh tones and to delineate the veins in her right hand. Her head, adorned with a white plume, tips gently to the left, and her grayish-blue eyes look directly at the viewer. Her brown hair is brushed back from her forehead and falls in curls onto her shoulders. She wears a white dress with a sheen that suggests satin. The neckline of her dress turns squarely at her shoulders and crosses her chest in a shallow arc that is decorated by three rows of pleated fabric. The bodice features a triangular panel that is outlined by pleats and is decorated with vertical stripes that appear to border stays. Horizontal creases at the girl’s sides suggest that the dress is laced in back over an undergarment structured with bones to promote upright posture.1 The bodice is crossed by a white sash that drapes from her right shoulder to her waist at her left side, where it passes through a loop. This sash is richly ornamented with fabric representing green leaves and tiny pink flowers. The sleeves end just below the girl’ s elbows in a six-inch ruffled band that is similarly decorated with leaves and flowers. The dress is completed by a striped white apron over a skirt patterned with Xs. The skirt billows widely. It and the apron are edged in front with pleated fabric, suggesting that the dress was once covered by an overdress.2

The chair Mary Ann Carpenter sits on has green upholstery and is edged with brass tacks. Earl used the same green to convey the fringed cloth that is draped over the table on the left side of the painting. The girl rests her right elbow on the table, and she leans a bit in that direction. Her right forearm turns back toward her lap, where her wrist bends softly and her hand clasps several flower stems: a large, circular purple flower with a yellow center, three tiny red blossoms with pointy petals and leaves, and another small purple flower. The girl’ s middle three fingers hold this bouquet, while her little finger lifts away from the others. Although Earl’ s drawing is a bit awkward, this gesture appears intended to convey the child’ s refinement. Mary Ann has a leather-bound book in her left hand. Her thumb is pressed on the back cover, and her index finger holds it slightly open. The book has six panels defined by gilt ribs on the binding, the second of which is a red title panel. Although the title is illegible, the flowers suggest that the volume may be about nature.

The walls behind her are defined in the same olive tones that Earl used in William Carpenter; they also demarcate a corner with a light surface to the left and a dark one that moderates to an intermediate tone to the right. A red curtain trimmed with yellow fringe fills much of the right side of the painting behind the sitter. The floor, visible only at the lower-left, is decorated with a patterned carpet that builds concentrically around a cross motif in two shades of brown, red, yellow, and two blues on a light-brown ground.

Biography

Mary Ann Carpenter was baptized on January 12, 1766, and so was thirteen years old when she sat for this portrait. She and her brother were the namesakes of their parents, Mary and William Carpenter. The senior Carpenter’ s social position was noted as yeoman at the time of the children’ s baptisms and "Gent[leman]." on his grave marker.3 The family lived near Norwich in Aldeby, Norfolk County, in eastern England. In 1784, when she was eighteen, Mary Ann married Thompson Forster. The couple moved to London, where Forster became a leading surgeon at Guy’ s Hospital.4

Analysis

Both this portrait and its pendant, William Carpenter; depict the children sitting in a room with a book. The drapery behind Mary Ann and on the table, the patterned carpet, and such ornate costume features as the feather in her hair and the floral sash combine to make this likeness considerably more decorative than the one of her brother.

The Carpenter home was about twelve miles from that of Captain John Money (1752–1817), Ralph Earl’ s first patron in England and the man who probably facilitated this commission. Money, who was quartermaster general to General John Burgoyne (1722–1792), had helped Earl flee New Haven for England in 1778, in the face of mounting pressures against him stemming from his loyalty to the Crown. In London, Money supported Earl’ s apparently unsuccessful plea to the Lords Commissioners of the Treasury for financial relief, and then seems to have brought the artist to his home, Trowse Hall, near Norwich.5

Mary Ann Carpenter reflects a clear development in Earl’ s sense of composition: he relates various elements in a way not seen in his earlier works. For example, the cross motif in the carpet subtly echoes the tiny surface design of the girl’ s dress. The artist pairs the complementary colors red and green in the swag of drapery behind the figure and the textile on the chair and table. The folds of the drapery, tablecloth, and dress further unite these elements. Earl relates forms elsewhere in the painting, too, as in the long triangle of the bodice and the inverted triangle defined by the cloth hanging at the front corner of the table. Even the diamond shape of the table, with its truncated left corner, is loosely mirrored by the negative space defined by Mary Ann’ s bent right arm, skirt, and waistline.

|

|

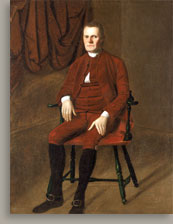

Figure 1. Ralph Earl, Roger Sherman, about 1775–76, oil on canvas, 64 5/8 x 49 5/8 in. (164.2 x 126.1 cm), Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut, Gift of Roger Sherman White, B.A. 1899, LL.B. 1902.

|

|

The perceived contrast between this composition and Earl’ s earlier American portraits, such as Roger Sherman (fig. 1), has led scholars to speculate on the artist’ s experiences in his first year in England. Most notably, the stark interior in the Sherman portrait stands in marked contrast to the one occupied by Mary Ann Carpenter. Indeed, the girl sits in a room that is more complex, colorful, and patterned than any Earl painted during his first American period. The art historians William and Susan Sawitzky were confident that Earl’ s improvement could only be explained by his having met and studied under Benjamin West, the expatriate champion of aspiring American painters in London. More specifically, the Sawitzkys saw in Earl’ s work of this time a direct debt to West’s Grand Manner portrait of Queen Charlotte (Collection of Her Majesty the Queen), a project that occupied the elder painter in 1778 and 1779.6 The patterned carpet, which became a common feature in Earl’s later Connecticut Valley portraits, first appeared as a motif in Mary Ann Carpenter. A similar geometric design is visible in the border of a carpet in West’ s portrait of the queen. Subsequent Earl and West scholars, however, have not found such formal evidence compelling. Both Elizabeth Kornhauser and Dorinda Evans have accepted the painter-historian William Dunlap’s claim that Earl entered West’ s studio "immediately after the independence of his country was established."7 The Treaty of Paris, signed on September 3, 1783, ended the American Revolution. In the views of Evans and Kornhauser, the pair of Carpenter likenesses appear to have more in common with Roger Sherman than with West’ s Grand Manner portraiture. The developments the Sawitzkys describe may be explained by Earl’ s exposure to the London art world rather than linked specifically to the influence of West.

|

|

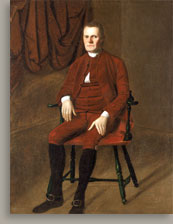

Figure 2. Ralph Earl, Marianne Drake, 1783, oil on canvas, 50 1/4 x 40 1/4 in. (127.6 x 102.2 cm), private collection.

|

|

The depiction of a literate girl holding a book is a prototype of female accomplishment that Earl called upon in works he subsequently painted both in England and America. Four years after completing Mary Ann Carpenter, Earl produced a three-quarter-length portrait, Marianne Drake (fig. 2), in which the young woman holds a watercolor landscape in her right hand and a brush in her left. A harpsichord is placed behind her, suggesting that she has been trained in music as well as the visual arts. Earl depicted her sister Sophia the following year, sitting under a tree and reading a book (Count Charles de Salis, Switzerland). The artist’s images conveying women’s intelligence and talents also include a portrait of his second wife, Ann, holding a map and seated next to a globe and a shelf full of books (Mead Art Museum, Amherst College, Amherst, Mass.), as well as portrayals of American women reading and doing needlework. In contrast to these representations of female accomplishments, many more of Earl’ s portraits of women show them holding children or decorative props.8

Notes

1. Aileen Ribeiro, costume notes to catalogue entry, Kornhauser 1991a, 115.

2. Ribeiro, in Kornhauser 1991a, 118 n. 7.

3. Louisa Dresser, curator at the Worcester Art Museum from 1932 to 1972, visited Norfolk, where she recorded Carpenter family gravestones and baptismal records. Her notes are preserved in the Worcester Art Museum object file and cited in Sawitzky and Sawitzky 1960, 39 n. 17.

4. See the Inscriptions section of this entry for the identification of the sitter as Mrs. Thompson Forster.

5. Ralph Earl to the Lords Commissioners of the Treasury, loyalist petition, January 28, 1779, as quoted in Phillips 1949, 187–89.

6. Sawitzky and Sawitzky 1960, 20. See also Von Erffa and Staley 1986, no. 556, pp. 469–71.

7. Dunlap I 1918, 264. Dorinda Evans (1980, 62–63) asserts that the first proof of West’ s instruction dates from 1784, while she allows for the possibility of Earl’ s prior contact with West. Kornhauser 1988, 53.

8. For women holding books in Earl’ s portraits, see Esther Boardman (1789, Edith and Henry Noss) and Mrs. Joseph Wright (1789, National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.). For women doing needlework, see Mrs. Richard Alsop (1792, National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.), Mrs. Charles Jeffery Smith (1794, The New-York Historical Society), and Mrs. Ebenezer Porter (Lucy "Patty" Pierce Merwin) (1804, The Brooklyn Museum, New York). These paintings are published in Kornhauser 1991a, 157–58 (Esther Boardman), 188–91 (Mrs. Wright and Mrs. Alsop) 194–95 (Mrs. Smith), 229–30 (Mrs. Porter). |

Ralph Earl

Ralph Earl