John Singleton Copley

John Singleton CopleyLucretia Chandler Murray (Mrs. John Murray), 1763

Description

Lucretia Chandler Murray (Mrs. John Murray) is a three-quarter-length portrait of a standing woman turned slightly right, facing three-quarters left, and looking forward. The woman’s brown hair is brushed back and falls in loose curls over her shoulders. Her oval face is brightly lit and has a shadow on the proper left side. The sitter has blue eyes that are shaped nearly as ellipses; the proper left eye is considerably larger than the right one. Her nose is narrow and her mouth curls in a faint smile. The flesh tones are primarily yellow, with touches of pink in the cheeks, forehead, nose, and chin, and white highlights on the forehead and tip of the nose.

By representing the body and head turning in opposite directions, Copley imparted a dynamic presence to this sitter. Mrs. Murray leans on a brown stone pedestal with a stepped top and a paneled front. Her left arm bends away from her body and her left hand hangs over the front edge of the pedestal. Mrs. Murray’s right arm crosses her body and her right hand rests gently on her left forearm.

The sitter wears a low-cut yellow dress that is decorated with white lace at the neck and sleeves and with lavender bows at the bodice and cuffs. The skirt forms an arc from the woman’s waist to the bottom left corner of the canvas.

The figure is posed outdoors in front of a dark brown stone ledge at left that supports a brown covered urn with gadrooned sides and a lion’s head mask. A wall behind the urn extends from the left edge of the painting to just right of the figure’s proper left shoulder. A loosely painted landscape in the upper right corner features a gently curving tree trunk that is arranged on a diagonal from Mrs. Murray’s left elbow to the upper right edge of the painting. The sky is blue and orange with touches of red near the horizon.

Biography

Lucretia Chandler was born July 18, 1730, the seventh of nine children of Judge John Chandler (1693–1762) and Hannah Gardiner Chandler (1699–1738/39).1 Originally from Woodstock, Connecticut (then part of Massachusetts), the Chandlers moved to Worcester in 1731 and were in every respect the most eminent family in Worcester County prior to the Revolution.2 John Chandler served Worcester as sheriff, register of deeds and probate, judge of probate, selectman, treasurer, and representative to the General Court of Massachusetts.3 Lucretia was not yet married when she went to Boston to care for the family of her recently deceased sister Mary Greene (1717–1756).4 On September 1, 1761 she married John Murray (1720–1794) in Worcester and moved to Rutland, Massachusetts, where her husband was a substantial landowner.5 Murray had ten children with his first wife, Elizabeth McClanathan (d. 1760), and in 1762 Lucretia bore a daughter who was named for her mother.6 Also that year Lucretia inherited three hundred forty pounds from her father.7

In addition to portraits by Copley, the Murray home was decorated with three pieces of rococo silver crafted by Paul Revere: a salver, a creampot, and a sugar bowl.8 All three pieces were decorated with the Chandler coat of arms, and the two hollowware pieces were elaborately chased with floral designs. The sugar bowl is inscribed "B. Greene to L. Chandler," indicating that it was a wedding present from her brother-in-law Benjamin Greene (1712/13–1776). When Lucretia died March 21, 1768, her husband gave gold mourning rings to family and friends that were inscribed with her name, date of death, and age.9

Lucretia’s husband was born in Ireland on November 22, 1720, emigrated to Massachusetts in the 1730s, and settled in Rutland about 1744.10 Murray made a fortune in land speculation and finance. He was elected a town selectman beginning in 1747 and a representative to the General Court of Massachusetts from 1751 to 1774.11 In 1755 he became a colonel in the militia and a judge of the Court of Common Pleas. John Murray married for a third time in 1770 to Deborah Brinley in Boston, and the couple had two children together.12 In 1774 Governor Thomas Gage chose Murray to be a member of the Council of Massachusetts, an appointment which nullified the popular election.13 Murray’s acceptance of a position granted by royal authority rather than the will of the people angered his townsmen and he was driven out of Rutland.14 He sought refuge in Boston and remained there until the British evacuated in 1776, at which time Murray moved to Halifax, and then London and Wales; he eventually settled in St. John, New Brunswick, Canada.15 In 1778 Murray was officially banished from Massachusetts and in 1779 his property totaling nearly thirty-one thousand pounds was confiscated by an act of the General Court.16 The British government granted Murray a stipend of two hundred fifty pounds per year as compensation for the losses he suffered as a Loyalist, and he settled permanently in St. John where he died on August 30, 1794.17

Analysis

|

|

| Figure 1. John Faber, Jr., after Thomas Hudson, The Right Honourable Mary Viscountess Andover, 1746, mezzotint, 12 1/4 x 9 7/8 in. (31.1 x 25.1 cm), Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, California. This item is reproduced by permission of The Huntington Library, San Marino, California. |

|

|

|

| Figure 2. John Smith after Sir Godfrey Kneller, The Duke of Gloucester, about 1693, mezzotint, 16 x 10 in. (40.6 x 25.4 cm), Trustees of the British Museum, London. |

Copley’s use of prints as sources was consistent with the practice of English and American painters at the time, and borrowing from them was common among such well-trained artists as Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792) as well as among the anonymous artisans who created overmantel landscapes in colonial American homes.20 The London-trained engraver Peter Pelham (1695–1751) was Copley’s stepfather and probably provided his first exposure to English mezzotints.21 John Smibert (1688–1751) and Joseph Blackburn (active 1752–1777)—both of whom trained in London and worked in Boston during Copley’s formative years—further exemplified the use of prints as sources for poses, gestures, costumes, landscapes, and still life elements within oil portraits. Quoting from prints implied the shared aesthetic knowledge of a sophisticated artist and sitter. Painters also used prints to limit the demands upon a sitter’s time and perhaps to help a patron visualize the composition at the beginning of the commission.

Copley found the print of the Viscountess Andover so useful that he used it as the basis for two more portraits: Katherine Greene Amory (Mrs. John Amory) (about 1763, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) and Mary Greene Hubbard (Mrs. Daniel Hubbard) (about 1764, Art Institute of Chicago).22 Mrs. Amory’s portrait follows the Faber mezzotint even more closely than Mrs. Murray’s, since it includes the putto holding a tablet that appears on the front of the pedestal and the drapery and sky in the background. Despite the resemblance of Copley’s figures and settings to their English sources, he individualized each sitter’s face. Copley also painted the lace differently in each of the three portraits, and the lace on Mrs. Murray’s dress even varies from one sleeve to the other.23 Copley’s portrait of Mrs. Hubbard is the only one of the three related paintings that includes a still life of papers on top of the pedestal, an element that appears in the Faber mezzotint. The most prominent page in the pile—the one hanging over the front edge of the pedestal—shows a line drawing of a flower and vine pattern, apparently indicating Mrs. Hubbard’s skill at needlework. The Viscountess Andover holds a porte-crayon and thus also appears as an artist. The sculpted relief of a putto holding a tablet reinforces the artistic theme of both the engraved and painted portraits.

The three women whose portraits Copley painted alike were closely related. Lucretia Chandler Murray and Mary Greene Hubbard were first cousins, as were Hubbard and Katherine Greene Amory. The Chandlers and Greenes were further related by marriage. Lucretia’s oldest sister Mary married Benjamin Greene, whose brothers Thomas and Rufus were the fathers of Hubbard and Amory respectively. Lucretia Murray was therefore sister to the aunt of the two other sitters.24 It may be inferred, therefore, that the three women chose to be portrayed in like manner as a means of paying tribute to their kinship.25

Lucretia Chandler Murray also sat to Copley for a double portrait with her twelve-year-old nephew Gardiner Greene (probably before 1761, destroyed). According to an early biographer of Copley, that portrait was three-fourths length, representing the lady dressed in a pearl-colored satin trimmed with rich lace, the hair without powder. She is seated with her right hand resting on the boy’s shoulder, while she holds his left hand in hers. The boy stands by her side dressed in a brown coat lined with blue silk. In his right hand he holds his hat.26 Gardiner Greene was the youngest child of Lucretia’s sister Mary and brother-in-law Benjamin Greene, whose family she lived with after Mary’s death in 1756.

|

|

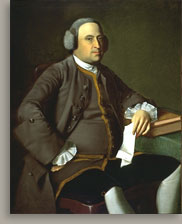

| Figure 3. John Singleton Copley, Colonel John Murray, about 1763, oil on canvas, 49 x 39 in. (124.5 x 99.1 cm), New Brunswick Museum, St. John, New Brunswick, Canada, Sir J. Douglas Hazen Bequest, 1959 (59.60). |

Notes

1. Sturgis 1903, 156; Chase 1905, 169–70 and 175–76; and Herbert H. Hosmer, a descendant of Lucretia Chandler Murray, to Jules Prown, April 6, 1982, object file, Worcester Art Museum.

2. Bowen 1930, III, 311; Sturgis 1903, 130; and Stark 1910, 392.

3. Chase 1905, 166–67.

4. Sturgis 1903, 156; and Clarke 1903, 149. Lucretia’s sister Mary Chandler Greene died in childbirth, February 28, 1756.

5. Sturgis 1907, 33–34; and Potter 1908, 20.

6. Coffin 1940, 239.

7. Chase 1905, 169.

8. Buhler 1972, II, 393–95.

9. For the mourning rings, see Ibid., II, 357. Her death was reported in The Boston Gazette & Country Journal, April 4, 1768: "On the 21st ult. died at Rutland, Mrs. Lucretia, the amiable consort of John Murray, Esq; in the 38th Year of her Age."

10. Potter 1908, 25; and Coffin 1940, 237–38.

11. Potter 1908, 15; Bowen 1930, III, 311; and Coffin 1940, 238.

12. Coffin 1940, 241.

13. Stark 1910, 376; and Coffin 1940, 242–43.

14. Stark 1910, 376.

15. Potter 1908, 24; and Hale 1989, 324.

16. "A Coppy of a Schedule of the Real & personal Estate of Jno. Murray Esqr, which he was Lawfully Seized and Possessd. of, on the 25 of August 1774 at which time he was forced to abandon it," London, November 1, 1783, J. D. Hazen Collection, Library/Archives Department, New Brunswick Museum, St. John, Canada. Information about John Murray and copies of archival material were kindly supplied by Andrea Kirkpatrick, Curator of Canadian and International Art, and Janet Bishop, Library/Archives Department, both at the New Brunswick Museum.

Although Murray’s property was inventoried in 1774 at the time that he was forced from his home, the General Court did not officially sanction the seizure until 1779. Potter 1908, 24; and Stark 1910, 377.

17. Potter 1908, 24 and 25; and Coffin 1940, 245.

18. Sweet 1951, 153; Fairbrother 1981, 123; and Lovell 1998, 21–22. Miles and Simon identify the source for Faber’s print as Thomas Hudson, Mary Finch, Visountess of Andover (1746, Greater London Council) (1979, cat. no. 26). Hudson, in turn, borrowed his composition from Hyacinthe Rigaud, Nicolas Boileau-Despreaux (Versailles), which was engraved by Pierre Drevet.

19. Trevor Fairbrother argues that Copley took the landscape at right in Lucretia Chandler Murray (Mrs. John Murray) from the left side of the mezzotint by John Smith after Sir Godfrey Kneller, Countess of Essex (about 1695, New York Public Library, Prints Division) and reversed it (1981, 123, 125, and 129). Fairbrother also proposes that the overall compositional structure derives from John Faber, Jr., after Thomas Hudson, Miss Hudson (British Museum, London.).

20. For years scholars have interpreted American portraitists’ borrowing from prints as evidence that colonial painters lacked access to formal training. More recently Fairbrother has argued that even at his most derivative moments, Copley "manipulated these sources to suit his pictorial needs" (1981, 122). Margaretta Lovell understands Copley’s use of prints as a mark of his sophistication rather than his limitations (Lovell, 1998, 22–23).

21. Prown 1966, I, 8–10; and Fairbrother 1981, 122.

22. Charles Willson Peale also borrowed from the Faber print of the Viscountess Andover in his Deborah McClenachan Stewart (Mrs. Walter Stewart), 1782 (Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven). Miles and Simon 1979, cat. no. 26, n.p.; and Sellers 1952, 202 and 299.

23. This observation was made by costume historian Claudia Brush Kidwell during a visit to the Worcester Art Museum, May 5, 1999.

24. Hosmer to Prown, April 6, 1982.

25. Lovell 1998, 28–29.

26. Perkins 1873, 63; see also, 88.