John Singleton Copley

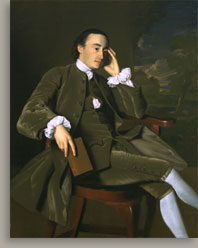

John Singleton CopleyJohn Bours, about 1760–62

Description

John Bours is a three-quarter-length portrait of a seated man facing three-quarters right. His dark brown, collar-length hair is combed back, showing a line of gray hair at the proper right temple and light brown highlights in the curls at the back of the head. The sitter’s dark brown eyes stare slightly down and to the right, creating a pensive mood in the painting. The flesh tones range from light pink on the forehead and chin to darker pink on the cheek and nose to red on the lips. Copley painted gray shadows in the face.

The man’s gestures contribute to the contemplative mood of the painting. The proper left arm bends sharply and the fingertips of the left hand rest on the face; the left elbow rests on the arm of the chair. Copley painted the proper left side of the face and the hollow of the cupped hand in shadow. Bours relaxes his proper right arm on the arm of the chair and holds a reddish-brown leather-bound volume in that hand. The right thumb is hidden from view and presumably holds the book open to a particular page; the extended index and middle fingers form a "V" on the cover and spine of the book. Copley used dark red and brown paint to define the shadows between the fingers of both hands.

Bours wears a brown velvet suit with matching cloth-covered buttons. He has wide ruffled cuffs and a shirt ruffle that is visible at the neck and through the partially unbuttoned waistcoat. The soft texture of the velvet is conveyed by subtle shifts from light to dark brown, especially along the gentle folds created by the seated pose. The breeches are fastened below the knee with a small square buckle, which Copley painted swiftly with white highlights over red brushstrokes. The white stockings were painted with zig-zagging strokes of paint that vary from bright white on the calf to gray in the lower areas of the leg. The edges of the sitter’s legs were painted with long vertical brushstrokes, and the right contour of the proper left leg was reinforced with a narrow dark brown outline.

The figure sits in a corner chair that is painted reddish brown and has a black upholstered seat. The two chair legs closest to Bours’s legs are both cabriole legs. The other two legs have a slight concave arch and are joined by a stretcher. The arched leg and the cabriole leg at the back of the chair are joined by a second stretcher.

The floor is reddish brown and the wall behind the sitter is olive brown. In the background at right, Copley included a loosely painted landscape with a group of trees, a winding body of water, and peach-colored clouds in a blue sky.

Biography

Baptized August 24, 1734 in Newport, Rhode Island, John Bours was the fourth of six children of Peter Bours (1705/6–1761) and Ann Fairchild Bours (about 1702–1789).1 He became a merchant and a prominent member of the Trinity (Anglican) Church and the Redwood Library. On July 7, 1762, John Bours married Hannah Babcock (1743–1796), who was the daughter of Dr. Joshua Babcock (1707–1783) and Hannah Stanton Babcock (1714–1778) of Westerly, Rhode Island. John and Hannah Bours had eleven children, six of whom lived to maturity.2 The Bours-Babcock marriage was probably facilitated by the fact that John and Hannah’s fathers each held prominent positions in the colonial government: Peter Bours was a member of the Council of Rhode Island, and Joshua Babcock served in the General Assembly and as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.3

John Bours was extremely active in the Trinity Church, serving variously as church warden, clerk of the vestry, and vestryman from 1765 to 1811.4 Bours’s father had been a member of the vestry of the same church from 1731 until his death in 1761. Many members of the Trinity Church were Loyalists who were protected by British forces between 1776 and 1779. When the British evacuated Newport in October, 1779, many of Bours’s fellow churchmen, including the minister, fled the town. The church became inactive until Bours served as lay reader from 1781 to 1786. In 1784 a committee was charged with choosing a new minister. They invited Bours to take orders and become the official minister, but he declined.5 In 1786 Trinity Church hired the Reverend James Sayre to lead the congregation. Two years later, Sayre fell out of favor with the people of Newport for his refusal to accept the authority of the Episcopal Church of America.6 Bours and Sayre clashed in a series of pamphlets in which the minister accused Bours of coveting the pulpit and Bours charged Sayre with promoting doctrines that resembled Catholicism.7

Bours was also a leading member of the Redwood Library, the center of eighteenth-century Newport’s intellectual life. In addition to serving as its treasurer, moderator, president, and as a member of the board of directors between 1761 and 1809, Bours donated a number of historical, literary, and scientific books to the Library.8 Bours’s father was a founding member and officer of both the Redwood Library (founded in 1747) and the Newport Literary and Philosophical Society (established 1730) from which the Library had developed.9 The elder Bours apparently encouraged his sons to seek knowledge. When John Bours’s brother Peter died, his obituary stated, "In his Youth, he laid a good Foundation for useful and polite Literature. . ."10 John surely received a similar education.

Bours was a merchant in Newport at the sign of the Golden Eagle at 185 Thames Street. He sold goods that were imported from Europe and the West Indies, including textiles, base metals, raisins, tea, coffee, sugar, rice, rum, wine, indigo, and spices.11 His business suffered in the years following the Revolution, as indicated in a letter that he wrote in 1786 to Metcalf Bowler (1726–1789): "The Paper Money, and the Act passed yesterday to enforce it—will in the Opinion of the cool & judicious, put the finishing Stab to all our Trade & Credit. —For my own part, look upon myself as ruined for never can I pay my Sterling Debt. —The Country is really in a most alarming State."12 Bours’s fortunes rose and fell again. When he prepared his will in 1813, he planned to distribute land and bank shares to his surviving children and grandchildren.13 He also intended to bequeath his share in the Redwood Library and his pew in Trinity Church to his heirs. The following year, however, Bours added a codicil in which he noted that "in consequence of the War, my Finances are greatly reduced and the means depended on for the Support of myself and Family rendered very precarious and uncertain." By September 1814, Bours’s situation had worsened and his monthly expenses exceeded his income.14 Bours died January 19, 1815.15

Analysis

John Bours is striking for its psychological depth. While the velvet and other materials depicted in the portrait demonstrate Copley’s characteristic virtuosity at representing textures, it is Bours’s absorption in thought that impresses the viewer. The sitter’s faraway gaze, gestures, relaxed pose, and book all contribute to the pensive air of the image. Copley enhanced the mood of the portrait with a strategic use of light and shadow on the face and proper left hand.

|

|

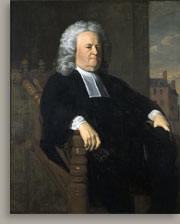

| Figure 1. Joseph Blackburn, Peter Bours, 1756, oil on canvas, 53 3/8 x 43 3/8 in. (135.7 x 110.2 cm), Courtesy of the Harvard University Portrait Collection, Gift of Miss Eunice Hooper to Harvard College, 1892. © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Harvard University. |

|

|

|

| Figure 2. Joseph Blackburn, Hannah Babcock, 1759, oil on canvas, 50 3/16 x 40 1/8 in. (127.5 x 102 cm), Worcester Art Museum, Bequest of George Nixon Black, 1929.23. |

Joseph Blackburn also painted a portrait of John Bours’s wife, Hannah Babcock (fig. 2), which was completed three years before Bours and Babcock were married. It is possible that Copley was commissioned to paint John Bours as a pendant to Blackburn’s Hannah Babcock (Mrs. John Bours). Each portrait represents a close-up view of a three-quarter-length figure with a loosely painted landscape background. That the two paintings are framed nearly identically in solid, shallow-carved frames further suggests that they may have hung in the Bours house as a pair. In one respect, however, these portraits are strikingly different: the introspection of John’s portrait contrasts sharply with the mood of whimsy and the emphasis on fashion in Hannah’s. Moreover, the probate inventory of Hannah’s father, Joshua Babcock, lists four family portraits which were probably the ones that Blackburn painted of Hannah, her brother, and her parents.16 That Hannah’s portrait was still in her father’s home in 1783 is evidence that Copley’s painting of John Bours was probably not conceived as a pendant to it. It is likely that both pictures hung together after that, as they descended in the family of their youngest son, Luke Bours (1784–1842), who settled in Charleston, South Carolina.17

The pairing of a female portrait by Blackburn and a male companion by Copley is found in other New England families of the day. For instance, Blackburn’s three-quarter-length Mrs. Epes Sargent (Catharine Winthrop) (about 1755, location unknown) preceded Copley’s Epes Sargent (1760, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.) in the same format; and a pair of half-lengths was painted by Blackburn, Catherine Saltsonstall Richards (1762) and Copley, John Richards (1770–71, both at Berry-Hill Galleries, Inc., New York, as of 1983). Blackburn’s Mrs. Thomas Flucker (Hannah Waldo) (1755) predates Copley’s Thomas Flucker (1770–72, both at Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine), but the two are in different formats. It is tempting to see Blackburn’s rococo style as a feminine counterpart to Copley’s more masculine realism. But the commissions may also reflect a shift in taste, the ascendance of Copley as the more esteemed painter, or simply Blackburn’s absence at the time the second portraits were desired.

Whereas Copley’s career was concentrated in Boston, it is possible that he traveled to Newport to paint Bours’s portrait. Copley had relatively few Newport sitters, but they included other members of Bours’s family: his first cousin Anne Fairchild Bowler (Mrs. Metcalf Bowler) (about 1758, Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine and 1763, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.) and his sister-in-law Rhoda Cranston (Mrs. Luke Babcock) (about 1756–58, University of Virginia, Charlottesville). Perhaps stronger evidence that Copley visited Bours’s hometown may be found in a number of his portraits that emulate Blackburn paintings that hung in Newport homes. For example, Blackburn’s Mrs. David Chesebrough (Margaret Sylvester) (1754, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) might have provided Copley’s inspiration for his Ann Gardiner (1756–57, private collection); Blackburn’s Mary Sylvester (1754, Metropolitan Museum of Art) appears to be a loose model for Copley’s Ann Tyng (1756, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston); and Blackburn’s Newport portrait John Brown (1754, John Nicholas Brown Center, Brown University, Providence) might be a compositional source for Copley’s John Barrett (about 1758, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri). However, both Blackburn and Copley borrowed from British print sources, which may also account for the coincidence of poses and themes in the two artists’ work.

Copley’s John Bours exemplifies a tradition of scholar portraits that dates to the Renaissance in northern Europe and became popular in England in the eighteenth century. Art historian Brandon Fortune recently traced that history from Jan Van Eyck’s painting St. Jerome in His Study (1435, The Detroit Institute of Arts) to Albrecht Durer’s allegorical engraving Melancholia I (1514, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D. C.), and to a series of baroque portraits including Anthony Van Dyck’s Henry Percy (about 1633, The National Trust, London) and Peter Lely’s Thomas Clifford, first Baron Clifford (private collection).18 The convention of an intellectual or a creative sitter depicted with a faraway gaze, one hand placed on the temple or chin, and an arrangement of books and papers was used in the eighteenth-century to portray George Frideric Handel (1685–1759), Alexander Pope (1688–1744), Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790), Horace Walpole (1717–1797), and Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792), among other notable sitters.19

|

|

| Figure 3. John Singleton Copley, Edward Holyoke, 1759-61, oil on canvas, 50 1/2 x 40 1/2 in. (128.5 x 102.8 cm), Courtesy of the Harvard University Portrait Collection, Gift of Mrs. Turner and Mrs. Ward, granddaughters of Edward Holyoke, 1829. © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Harvard University. |

The date 1760–62 for John Bours is also supported by technical comparison to Epes Sargent (about 1760, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.); Copley painted both of these portraits with direct, wet-on-wet brushstrokes rather than with the thin glazes that he favored in the mid-1760s. Mary and Elizabeth Royall (about 1758, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) is another early example of the artist’s direct application of paint, although the draftsmanship and blending of wet-on-wet paint appear cruder in that portrait than in John Bours.22 Copley’s direct technique is not a definitive dating tool, since he returned to this approach later in his American career.

The biography of the sitter offers two occasions that further support the proposed date for the portrait: Bours’s father died in 1761, leaving John property and money, and Bours married in 1762. Both inheritance and marriage marked a man’s coming of age in the eighteenth century and commonly preceded a portrait commission.23 The frame in which John Bours hangs also offers a clue as to the painting’s date. Similar frames appear on thirteen other portraits by Copley; two of those were done about 1760–61 and nine were painted in 1763 or 1764.24

Finally, the objects represented in John Bours may hint at the date when Copley painted it. Velvet was in style for men in the 1760s, but was more commonly worn by older men in 1770.25 In the early 1760s Bours imported textiles from London, such as one shipment in 1761 that included "superfine scarlet, blue, black, and claret-colored broad cloths, German and embossed serge, green and cloth-coloared ratteen, thicksets, knit breeches, patterns, black, blue, and drab-colored cotton velvet. . ." (emphasis added).26 It is worth noting that in 1761 Bours was selling velvet similar to the fabric of his suit in the portrait. Still, Bours clearly wanted Copley to represent him as one who cared more about the pursuits of the mind than the latest fashions.27 For example, Bours sits in a Queen Anne corner chair of a type that was popular in the 1740s, rather than a more fashionable Chippendale-style chair.

Notes

1. Gene Clears to Susan E. Strickler, August 9, 1983, object file, Worcester Art Museum.

2. Ibid.

3. For Peter Bours’s political position, Updike 1907, II, 27; for Babcock’s public offices, see Brown 1909, 16.

4. Mason 1890, 132 ff; Updike 1907, II, 288–89.

5. Mason 1890, 165.

6. Updike 1907, II, 170–71; and Mason 1890, 184 n. 202.

7. The conflict between Sayre and Bours appears in Sayre 1788; Sayre 1789; and Bours 1789.

8. For Bours’s offices in the Redwood Library, see Mason 1891, 7 ff. Maris S. Humphreys, Special Collections Librarian, Redwood Library and Athenaeum, to Laura K. Mills, December 15, 1998, identifies the books donated by Bours as: Tobias Smollett, Continuation of the Complete History of England , vols. 12–15 (1760–61); Jonathan Swift, The Works of Jonathan Swift, vols. 13–16 (1764); Royal Society of London, Philosophical Transactions, five vols.; David Hume, The History of England..., vols. 5–6 (1762); and J. L. De Lolme, The Constitution of England... (1790).

9. For Peter Bours’s role in the Redwood Library, see Mason 1891, 12 and 34.

10. The Boston Evening-Post, November 9, 1761.

11. The Newport Mercury, September 18, 1759, April 28, 1761, March 23, 1762, May 27 and August 19, 1765, March 24 and July 21, 1766, June 15, 1767, and July 2, 1808.

12. Metcalf Bowler was the husband of John Bours’s first cousin Ann Fairchild (1730–1803). Bours to Bowler, June 30, 1786, John Hay Library, Brown University, Providence. The library contains two other letters from Bours to Bowler, August 24, 1786 and April 12, 1788.

13. John Bours, Will, April 23, 1813; Codicils, January 26, 1814 and June 20, 1814, Newport Probate, v. 5, pp. 229–32.

14. John Bours, Portsmouth, Rhode Island, to Stephen Gould, Newport, September 5, 1814, Redwood Library and Athenaeum.

15. Bours’s obituary in the Rhode-Island American & General Advertiser, Providence, February 3, 1815, reads: "DIED, At Newport, in the 81st year of his age, JOHN BOURS, Esq. for many years a respectable merchant of that town."

16. Inventory of the estate of Joshua Babcock, April 9, 1783, Westerly Town Clerk’s Office, Westerly, Rhode Island.

17. Rhode Island Vital Records X, 1898, 483 and XIX, 1910, 361; "Bours Family," typescript, object file, Worcester Art Museum.

18. Fortune and Warner 1999, 20–24 and 50.

19. Stebbins 1995, 88–89; Paul Staiti, "John Bours," in Rebora 1995, 266; and Fortune and Warner 1999, 28–29.

20. Jules Prown dated the painting 1759–61 by comparing its composition and palette to other contemporary works (1966, I, 33–34). Former Worcester Art Museum curator Susan E. Strickler proposed a date of about 1765–70 for the portrait (Worcester 1994, 181). Paul Staiti argued for a later date, about 1770, based on a group of psychological portraits painted at that time (in Rebora 1995, 265–66); see also, Stebbins 1995, 89, and Barratt 1998, 14–20. Barbara Neville Parker and Anne Bolling Wheeler dated John Bours about 1763 (1938, 39). Finally, the catalogue of an early exhibition of Copley’s work suggested that the painting was done "about 1774?" (Metropolitan 1936, cat. no. 36), apparently based upon a letter from Adam Babcock to Henry Pelham, December 24, 1774, that mentions John Bours in an unrelated context (Copley-Pelham 1914, 281–82).

21. Prown 1966, I, 33–34.

22. Rita Albertson, paintings conservator at the Worcester Art Museum, suggested the comparison to Mary and Elizabeth Royall, a portrait on which she did conservation work in preparation for the 1995 Copley exhibition.

23. Lovell 1994, 287.

24. Heckscher 1995, 145 and 158 n 11.

25. Costume notes are based on a conversation with Claudia Brush Kidwell, May 3, 1999.

26. The Newport Mercury, April 28, 1761.

27. Staiti 1995, in Rebora 1995, 264–66.